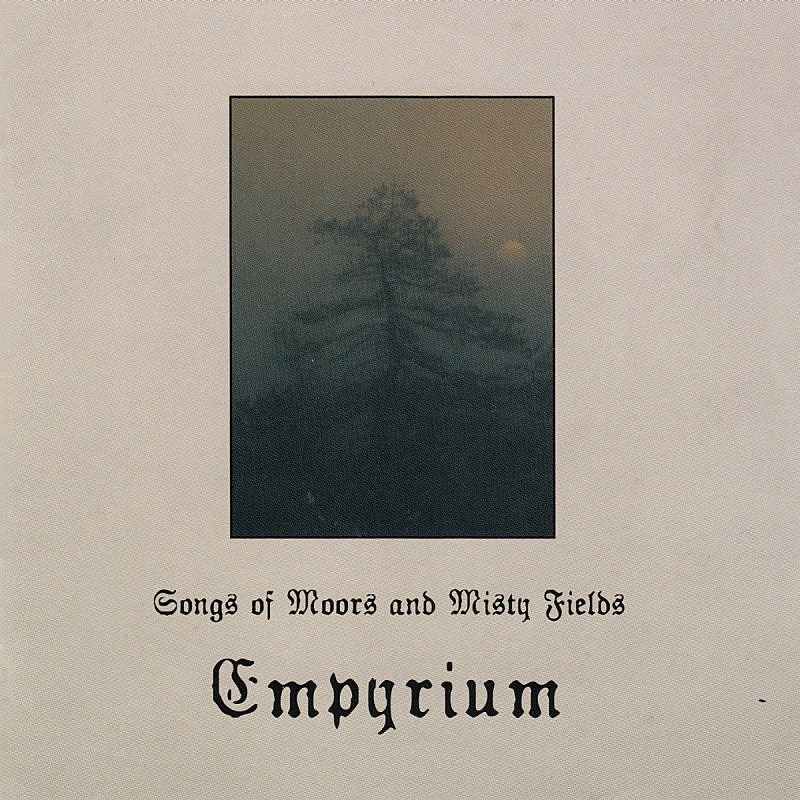

Many a Sun Has Set: Markus Stock Reflects on Empyrium 20 Years after "Songs of Moors and Misty Fields"

…

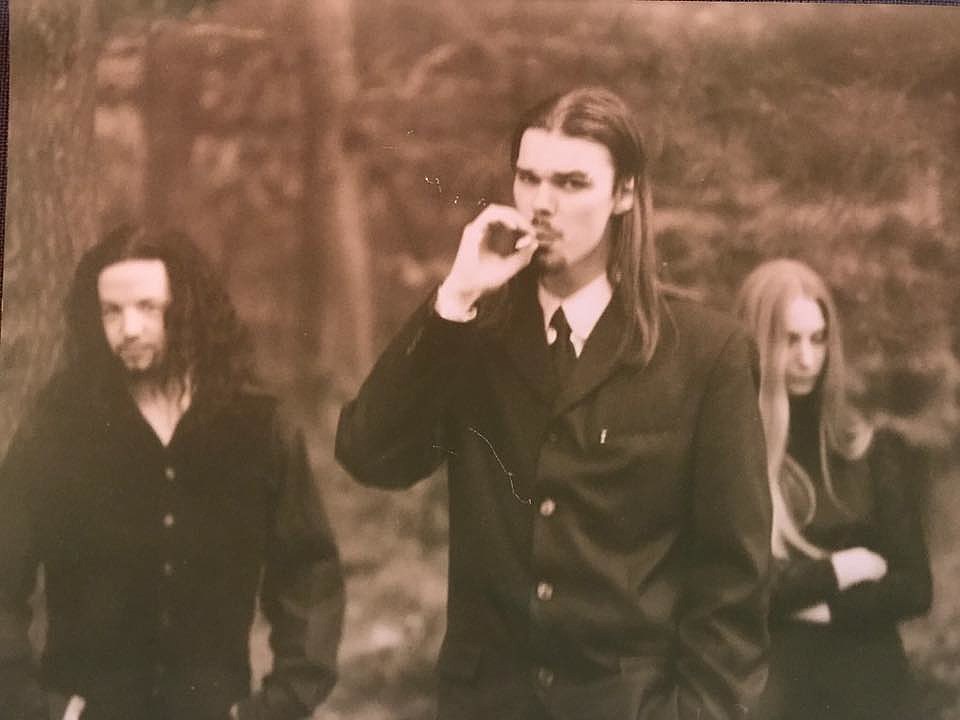

Empyrium’s first two records are what some might call “pivotal.” The musings of two isolated artists — Markus Stock, later known by his nom du plume “Ulf Theodor Schwadorf,” and Andreas Bach — this project’s imparting of gothic and romantic sensibilities to a then-unique fusion of neofolk and doom metal created an outpouring of global creativity, cited as a major influence by bands like Agalloch, Ningizzia, Alcest (whose Neige would eventually join Empyrium’s live lineup), Uaral, and more. Though bands like My Dying Bride and Paradise Lost communicated similar gothicisms in their music, Stock and Bach’s own style espoused a more pastoral elegance.

Much like how the age of nature-inspired, transcendental folk music followed the Romantic era, Empyrium took the lacy, Victorian sounds of the classic Peaceville 3 era and transported them to the countryside. The project’s last outing as a metal band before their 2014 reformation, the intricacy and rumination found within Songs of Moors and Misty Fields lives on in its own singular nature, even 20 years later.

…

…

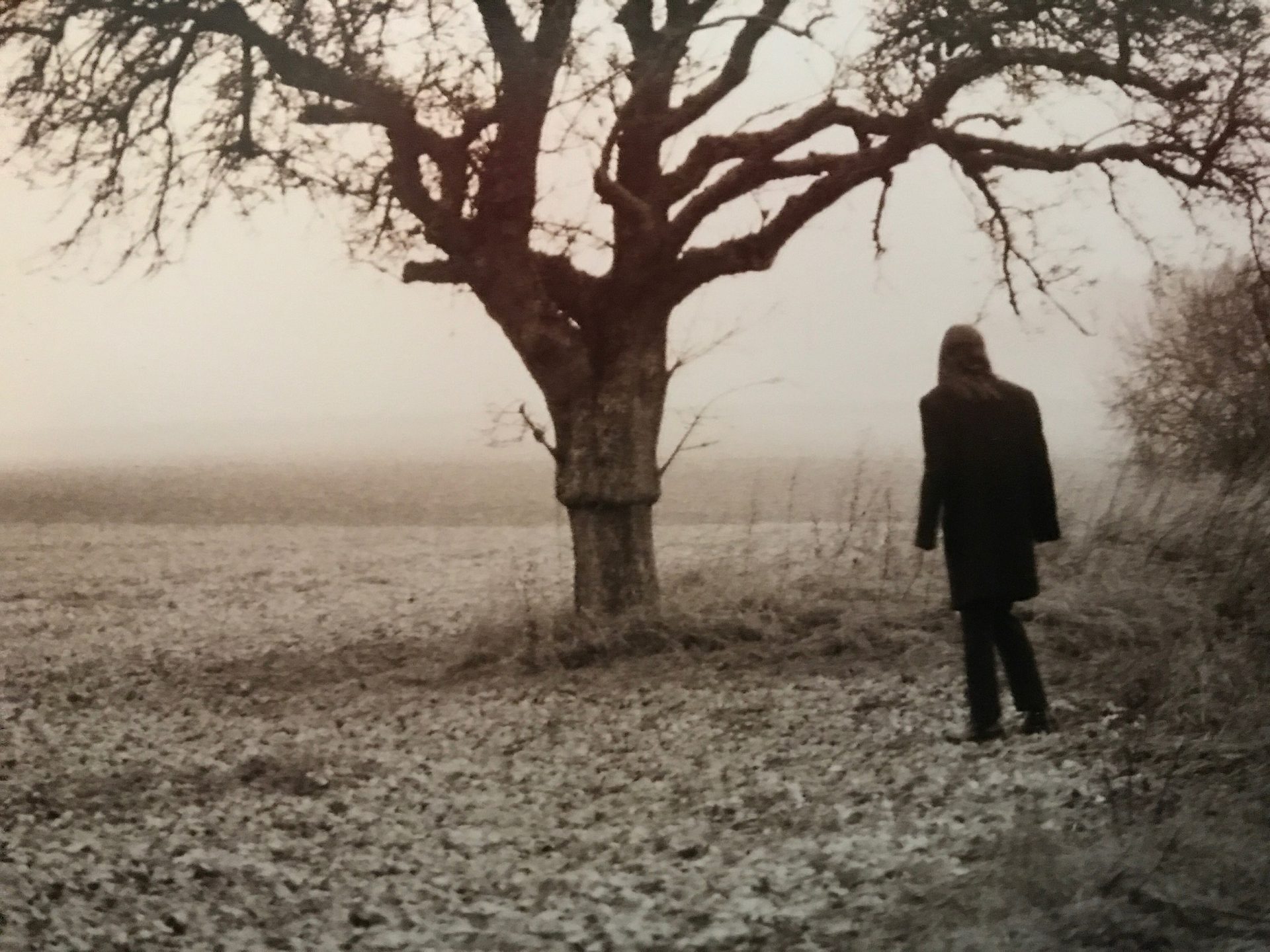

As the album’s title would suggest, so delicately represented in the sepia-toned cover artwork, Empyrium celebrated the inherently gothic imagery of fog-drenched fields and depictions of the jilted, tragic lover traipsing across the moors. Equally dramatic in sound, Stock’s carefully crafted melodies, deliberately paced and shimmering, painted melancholic sonic depictions of nature and lost love. Though titles like “Ode to Melancholy,” “Lover’s Grief,” and “Mourners” appear obvious given the context, the performances found within are wholeheartedly genuine and chilling, as if the artist truly experienced the old stories and tales of loss spun therein.

Songs of Moors and Misty Fields opens and Stock plays the bard, setting a twilit scene of desolation and crepuscular mist rolling over the hills:

When shadows grow longer

and the sun sets for the forthcoming night;

our sorrow is stronger

as darkness and death are now near by our side.

Many a sun will set and tears of grief will be shed…

Though erring on the dramatic, the visual element here is undeniable, and the narrator’s own loneliness is brooding, but Stock’s own communication is unassuming and lacks pretense. This restraint sets the stage for the album as a whole — even through the performance’s bombast and theatrics, Stock’s presence as chorus and tragedian never fully ventures into the uncomfortable and comical.

There is a much more pronounced folk and neofolk presence on this particular album, undoubtedly setting the stage for Stock’s future and strictly neofolk collaborations with tenor Thomas Helm on Where at Night the Wood Grouse Plays and the Weiland double album, but there is still a natural cohesion between Empyrium’s identity flux which cements this particular album’s placement in a higher pantheon of folk-influenced metal. The small flourishes found within classical guitar interludes, or keyboard player Andreas Bach’s own consistent presence sculpts this experience with striking melodies following each other in constant succession. An album of many “earworms,” Songs of Moors and Misty Fields solidifies itself in a special sense of dramatic catchiness, a timelessly memorable listen which fueled the impetus of Prophecy Production’s own “eerie, emotional music” slogan.

…

…

To so quickly follow its predecessor (released just a year prior) is surprising, even in hindsight. Considered a classic by many, A Wintersunset… was a powerful opening statement, more metallic and immediate, manifesting Stock’s own career in aggressive tragedy. However impressive (and, yes, I was so deeply under the spell of Empyrium’s debut for quite some time), the years which passed have slowly revealed this sophomore effort to be the masterwork lurking deep within its older sibling’s shadow. Songs of Moors and Misty Fields‘ own lurching, orchestral sound unveils a sudden maturity and thoughtfulness which had only been hinted at on Empyrium’s debut. On this second album, Stock was able to take the band’s then-established lyrical approach and build upon it with a much more confident songwriting. Now letting his music flow, with these very emotive melodies taking center stage, ideas became longer and shifted in staggered motion; the melancholy presented on Songs of Moors and Misty Fields is more palpable and possesses a lasting character, gluing itself to the listener with a lingering effect.

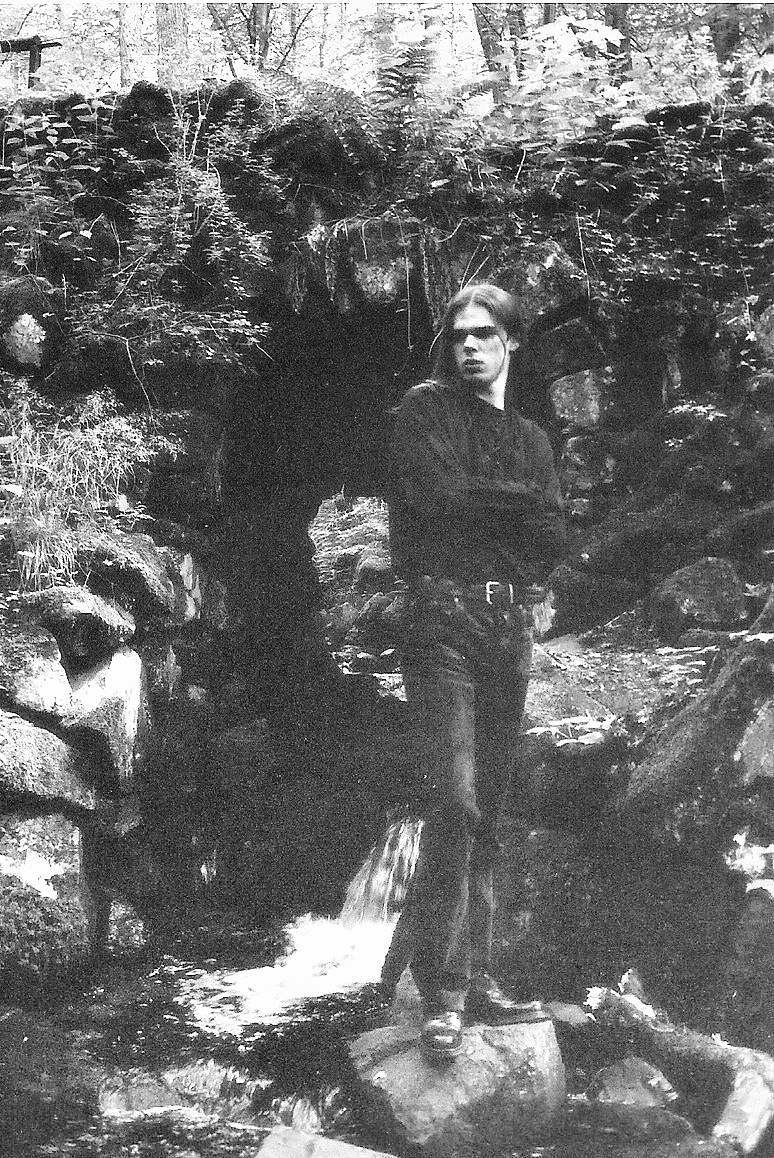

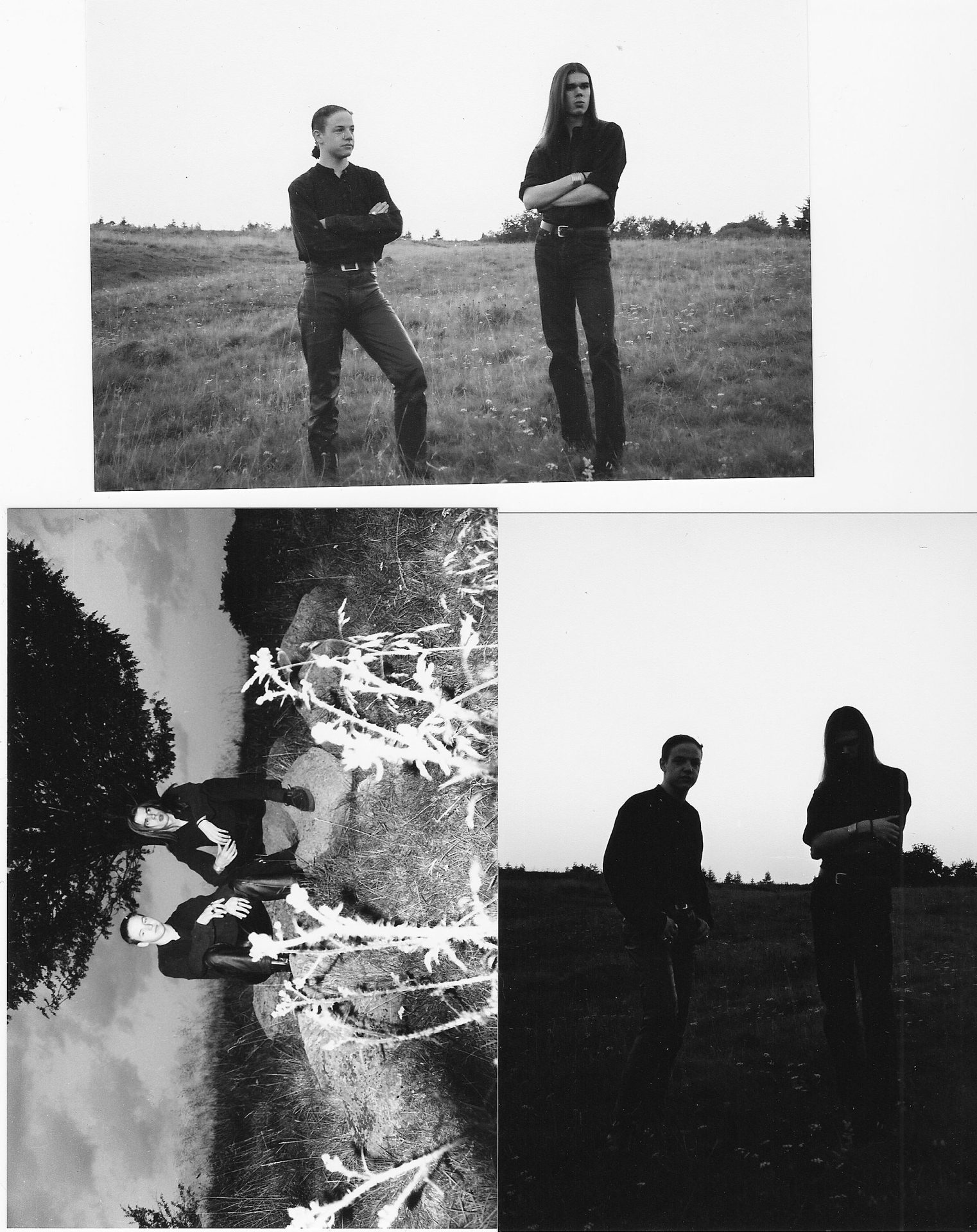

Even now, as I revisit this particular album so long after first hearing it almost 15 years ago, these songs have truly stuck with me. Stock, Bach, and flautist/cellist Nadine Mölter’s greatest, final triumph as a metal band forced themselves through the singularity and into eternity. There is nothing quite like this album, which his the two decade milestone on November 18th, and an ocean of artists owe their entire careers to Empyrium’s living legacy. I had intended to discuss Songs of Moors and Misty Fields with Markus Stock, which quickly devolved into a lively discussion of the band’s entire lifespan in past, present, and future. You can read the full retrospective interview, complete with a few never-before-seen photos from Empyrium’s first era, below.

…

Interview with Markus Stock

I actually haven’t listened to the record in its entirety for quite some time. You know, with Empyrium lately we have been playing the songs live quite a lot, so I’m very very familiar with the record and also the time when we recorded it. It was a very special period of time in my life.

I remember when the first videos of your first concert had surfaced and you played “Mourners.” That was particularly moving for me.

Absolutely! For me, as well, you know! I really remember when we rehearsed “Mourners” for the first time with the full band, it was really uplifting this was the first time I had really heard the song in a rehearsal kind of situation. Obviously in Empyrium we were always only two guys, so we never rehearsed the song as a band. It was always more or less in our minds and on the Fostex 4-track cassette recorder back then where most of the stuff was composed. When we rehearsed “Mourners” for the first time, it was really uplifting because it was the first time I’d heard it played by a band.

It was particularly stirring to see people like Jochen [Stock, of Dornenreich] and Neige [of Alcest] onstage with you, as well. Just this very big culmination of artists whose music I admired.

Yes! These two guys are one of the reasons that this happened. When I recorded an Alcest album with Neige, he kept telling me he was really into the old Empyrium stuff and he would love if the band played live one day and I should immediately give him a call if it happened, stuff like that. The same with Jochen, I remember he wrote me back in like… 1998 or something. He told me he was a huge fan of Empyrium. I met him for the first time in 1999, and this was a big part of the concept of playing live with Empyrium, to only invite musicians who I admire, myself, as well, and I know were really into Empyrium.

…

…

Now that it’s been twenty years since the album was released, does it feel like it’s been that long?

It’s always hard to tell. In a way it feels that long because of course I was, what, I was 17 or 18 when we recorded it?

Oh my god.

Yeah [laughs]. I was really young! Now I am 39 and am in a totally different situation in my life, but the emotions and everything in this album are… I would even say truer to myself than ever. It’s almost as if some of the stuff on this album, especially the lyrics as this young guy with not so much experience in life… the older I get, the more I find these lyrics are really, really wise in a way, which is weird because back then I didn’t have so much experience in my life. In some ways, it doesn’t really matter, you know, because when I wrote these lyrics and when we wrote this album, I was so much into what I was doing. Empyrium was a 24-hour job for me back then. I was doing nothing else. I’d quit school half a year before, my parents hated me for that, of course. I told them I was becoming a musician and we were opening a recording studio the next year, so I don’t need school anymore… and I quit school!. I took half a year composing from morning until evening, then meeting with Andreas [Bach] in the evening since he was working a job at the time. We would go through songs. It was really a time that was so focused. Wait, what was the question again?

[laughs] You pretty much hit the nail on the head! You seemed so entrenched in it and have so many vivid memories of the time.

Absolutely!

I always found it interesting since it came so quickly after A Wintersunset…. It’s such a sophisticated record, especially knowing you were just 18 when it was recorded. I mean, now knowing you were writing it 24 hours a day, it seems like it such an intense process.

It was super intense! I remember… it all started when we released the demo [...Der Wie Ein Blitz Vom Himmel Fiel..., 1995] I think in 1994. I think this period from 1994 until 1999 was definitely the period where I was most focused on something ever in my life. When we recorded the demo tape, for example, we were these two loners from the countryside. All contact I had with the scene was only with letters and tape trading from fanzines and stuff like that, so when we recorded our music we thought, “Yeah, it would be cool if we could get a review in Voice from the Darkside or something!” Just so we could have our name in there, you know? Yeah!. Then we got this praise from everywhere like that fanzine, all the fans replied with interview requests. It was amazing! We were so euphoric by these reactions! Then with A Wintersunset… we were little…too euphoric [laughs]. I have a lot of great sentiments for this record as well, and I really loved it, but it was a little too much on the sweet side for me. This was something I wanted to erase with Songs of Moors, you know? I wanted to make this record [without] all the mistakes we made on A Wintersunset…. They were not going to be on Songs of Moors. I wanted it to be this classic opus.

As I have been spending more time with this record this year — for the first time in eons. I guess the first four Empyrium records really defined my youth. Now, returning and listening to the two metal records, I noticed there is this huge leap in style. Like you said, it’s not as sweet, it’s more somber. The whole record is dedicated to melancholy, after all.

Absolutely. I think it’s more somber, more serious. No… not serious… more solemn, in a way. This is because of the mistakes I felt we made with A Wintersunset…. I know there are lots of people who disagree, and there is a big following for A Wintersunset… and I don’t want to bash the record as it is a part of my musical life, as well, but Songs of Moors, for me, was something different. It was from autumn 1996 until summer or August of 1997 when we recorded it… I was just coming out of a bigger depression in my life. I had started working and I hated it with all my heart. No, wait, I’m mixing shit up! That came after Songs of Moors!

[We both laugh]

No, this was after I quit school in the autumn. Yeah! I was really super focused on this. Nowadays, in these Internet times, I don’t think most younger people now know how the underground worked back then. Sometimes I spent a whole day writing letters and sending packages throughout the whole world. This was part of the process of making Empyrium so well known in the underground back then. It was like a day job, or a day and night job. I did nothing else, running Empyrium from my childhood bedroom at my parents’ place. I had nothing else in my head, nothing else… except maybe some alcohol every now and then.

…

…

It is especially interesting to think about the way the metal scene works now in comparison to how it was back then. I kind of came in at the tail end at the mailing CD-Rs era. Now it’s all about Bandcamp and the world seems so much smaller.

Not just smaller, but also less interesting. Sometimes people listen to 30 seconds of music. “Listen to this! Boom!” What can you say about music after just 30 seconds? Back then you ordered a record, you waited for it, and then it arrived. If it didn’t click at first listen, you made damn sure you listened again a couple more times to make an opinion. Now people try to make opinions about records, or everything in life, in less than ten seconds! How is that possible? It’s just cramming!

I suppose I can’t comment on that since I tend to do that now. I’m definitely one of the worst in that respect.

[We both laugh]

I mean, I just joined Facebook last year as a private person. Before then, I just ran the band account and now it’s just…[groans and mock spits]. There are some days when I just want to throw out my mobile phone. It all just makes me so angry, what I read online. I suppose I get mad even at the news, so I guess it doesn’t make a difference.

So, going back to the album. I’ve noticed in that particular time period, Empyrium was very singular. There wasn’t really any music quite like it beforehand. There was gothic and romantic music that other metal bands had taken on, like the Peaceville bands and Ulver, but I guess you had co-existed with Ulver in that period. What inspired you to make music like that? Something that hadn’t really existed before it?

I really… don’t know… exactly. What I do know is I always composed music, to this date, that I really love to listen to. I have a really broad musical taste, I always have. I am a metalhead, always have been, but I have always liked stuff like Loreena McKennitt, Dead Can Dance. The more arcane, more ethereal music, as well. I think Empyrium is still, and back then was, as well, just the music I wanted to listen to. The mix of all these influences and music that I loved, and we mixed it all together and made this music which came straight from our hearts. This is why it is so unique. Like I told you, we were two guys from the countryside, and there was absolutely nothing around us. We didn’t have any clubs or anything social. When we went to concerts, we had to drive for two hours. I think we were very isolated, so we just did what we wanted to hear from other bands, which is why it turned out so unique.

You brought up Loreena McKennitt and other darkwave, which is an interesting connection. When you approached mixing the darkwave and the gothic sensibilities of the aforementioned artists with the metal you liked, there was the intent since you said it was coming from your heart, but, when you were writing it, were there any obstacles you felt you had to conquer since there wasn’t any precedent?

The biggest obstacle was recording and performing the clean vocals, like on A Wintersunset…. We recorded it in a professional studio, and there was no Pro Tools back then. There was just two-inch tape and there wasn’t the multiple take process where we cobbled the vocals together various takes. Back then, it was always “one takes” — there was one part since we didn’t have much time then there was another. Maybe one take wasn’t the best [vocal wince], but maybe we could fix it when we finished, even though we didn’t have time to actually fix it. The biggest obstacle was putting the clean vocals into our sound, since I wasn’t the most experienced singer, obviously, but we really wanted it to be a part of our sound. Since you mentioned “wave bands,” there was this one German wave band, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard it, called Daine Lakaien. The vocalist, if you listen to him, you will find where I found the inspiration for my voice, it’s very obvious. I loved this band back then!

Well, I’m curious!

I will send you a link and then you will laugh your ass off when you hear it.

I mean, I certainly have a high threshold when it comes to “gothic vocals.” We’ll have to see how that goes.

Well, I love the vocals but you will laugh your ass off when you find out how much I ripped this guy’s voice off!

…

…

There was certainly a lot more in confidence on this second album in your vocal performance on this second album: bigger vocal harmonies, you were getting more extensive with your range. Was this just from practicing?

Yeah, this was from practicing a lot and from having the doubled time in the studio. With A Wintersunset… we recorded 4 days in the studio and mixed in one day.

Wow.

Yeah, there was essentially no mix. On Songs of Moors, we had ten days, which is doable. Nowadays, I can record a band in ten days, so this means you can put a little more effort and more work to see if a take is good or not. I think this, and one more year of experience and practicing the clean vocals gave me a lot more confidence when actually performing them. I also knew much more of what I wanted from them. On A Wintersunset…, we just knew we needed clean vocals, so I knew I had to try them. On Songs of Moors, I knew what kind of direction I wanted the clean vocals to be in and what kind of atmosphere they should add to the sound.

Speaking of you saying you knew what you wanted, I noticed there were a couple different kinds of characters that you played throughout the album. There was The Bard in the beginning and when you made the omniscient kind of narrations, then there was the Tragedian, the actual character, then there was the voice of the Night… was this something you intentionally did, or did it just kind of happen?

It just happened, there was nothing that really “thought out” beforehand. This always happens when I realize I did something great. I never put too much thought into it, but my subconsciousness works a lot. It puts these things together without you realizing what you’re doing. Just following your instinct, following the music, following the flow of the record and what it’s supposed to be. In the end, you realize it all fits together by magic arrangement and you don’t know how it happened. This is how, speaking for myself, when these arrangements come so naturally and you realize there is a bigger picture to the record. This always happens in subconsciousness, never something I ponder about beforehand. You just have to go with the flow of the album that you create.

…

…

It’s always fun to figure out something you made is much more mature than you expected it to be, I guess.

Yeah, especially looking back, you know? I never realize this when an album is finished or even a month afterward. You don’t have the distance, but now, 20 years later, there isn’t much (aside from the small details) that I would change. The big picture is just perfect.

Absolutely. There is a lot going on. Even now, after listening to the record for almost 15 years at this point, I still find a lot of enjoyment. There’s a lot of nuance. It’s a special album, I guess you could say.

This is exactly what people keep telling me over and over, as well. You said you spent your youth with the first four Empyrium albums, and so many people tell me that it’s almost frightening.

It’s hard to look at things you create with that kind of perspective, especially when you made it when you were so young.

Exactly. It’s like when we played Turkey last year It was sold out, two days in a row in Istanbul. People were going crazy, the Turkish TV was there. People kept telling me “Oh Empyrium! We grew up with you!” It’s really… what the fuck is going on? I made this from my childhood room and it spread into every corner of the world. It’s so amazing.

That’s a special sort of experience to have. I guess I can’t put it into my own perspective as I haven’t made that much music. I keep using the word special, but it certainly is.

Absolutely. The Istanbul people tell me it was really unique and special.

Diving back in, you certainly changed your lyrical approach on this record. Looking at the lyrics for A Wintersunset…, they were a little more plaintive and certainly emotive, but on the second record you went for something a little more… I guess Middle-High English? You went for something a little more akin to Shakespearian poetry. What was it like trying that approach to English out, especially since you were a young kid from the countryside?

I think it was the fault of stumbling on some poems by Lord Byron. He is a big inspiration for me since the first day I read his stuff. I think the first thing I read of his was from his drama Manfred.

When the moon is on the wave,

And the glow—worm in the grass,

And the meteor on the grave,

And the wisp on the morass;

When the falling stars are shooting,

And the answer’d owls are hooting,

And the silent leaves are still

In the shadow of the hill,

Shall my soul be upon thine,

With a power and with a sign.

This was the first I read from him. Years later, in 2010, we used this as an introduction for a The Vision Bleak album [Set Sail to Mystery]. I figured it was time I opened the source from where I stole so much. I was so intensely inspired from Lord Byron. Edgar Allen Poe, of course. Shelley, Keats… I read all this Romantic literature from Britain and the USA.

Another thing that really inspired me was Cradle of Filth. The lyrics by Dani Filth back then were so fucking amazing, and still are. I still think he’s one of the best lyricists in the metal scene. People nowadays see the gothic imagery and think, “oh, fine,” but there was really a lot of depth into what this guy is doing. The lyrics for The Principle of Evil Made Flesh were really an eye-opener for me, what you can do by combining great lyrics and great music.

Of course, Ulver’s Bergtatt was really eye-opening as far as its concept and everything. These kinds of sources were what made me really try to get the lyrics as good as possible. Like you said, A Wintersunset… had very emotive, I guess what you could say a little bit teenager kinds of lyrics, in a way. Really emotive, but awkward here and there. On Songs of Moors, I didn’t want this to happen. I’m not saying I wanted it to be like Lord Byron, this would be ridiculous, but I at least wanted it to be poetic.

Definitely. I still find an incredible amount of depth when I look into these lyrics. Some might verge on melodrama a bit, but that’s also kind of the point of these kinds of romantic poetry.

Of course, it is. The essence of romantic poetry and literature is the larger than life lyrics and poetry. Emotion is always over the top. Of course, this is something that balances with life. It’s funny, some of the big romantic poets in Germany, like Novalis, for example, he was an accountant in his day job. I think this is why his poetry was so emotive, it was a balance in his life. Being an accountant in his day job and a great Romantic poet in the evening. It’s all about balance in life! I don’t know if this makes my life boring or not…

I don’t know, your life seems pretty exciting!

[Laughs] I don’t think so, but, you know, I think everything you do in art is a reflection of your life and what you want it to be.

It seems like you really wanted to be this sort of Romantic hero when you were a teenager.

Absolutely. A Byronic hero, for sure. Absolutely.

…

…

Before you and Thomas [Helm] ended up reforming the band in 2010, this was the last metal album Empyrium made. Was this planned out, or did it just kind of peter out?

It really… just happened, due to a lot of circumstances. First off, I started listening to a lot more folk music after Songs of Moors was done. Kveldssanger, when I heard this record, I knew I had to do something like this. Tenhi, from Finland, was a huge influence after Songs of Moors. Also, me and Andreas [Bach] chose different paths in life. I wanted to focus more and more on music and its atmospherics and seriousness. He wanted to integrate more catchy… I guess more gothic rock stuff, which I later did with The Vision Bleak later on, oddly enough. He wanted to move into this direction, and he got busier with his job while I did Empyrium 24 hours a day. I sort of knew this would happen, that we would break apart as a band. It happened early in 1998, I guess, and this was the same time I decided I wanted to do an acoustic-only mini CD, but it, of course, turned out differently and this was the direction Empyrium ended up taking. This wasn’t planned, though, and there was never a thought when we recorded Songs of Moors that it would be Empyrium’s last metal record. We still were totally into the style and Andreas and I still were best friends and lived with each other. Back then, it was truly never a big plan to move away from metal.

Was there ever any regret in moving away from the metal style?

I think after Weiland, yes. Maybe not regret, I think that’s the wrong word, but I began to miss metal in my life. I remember in 1998, around this time, was when more metal began to sound so plastic, and I really hated it. All the triggered drums… I grew so tired of metal in a way and I wanted to do something more… like what I listened to. Neofolk. I thought back then, which is ridiculous now in retrospect, that metal was inferior. I hate that thought, and feel totally different now. It’s totally not like that, but back then I felt that way, so I chose to move in a more acoustic route in the Where at Night and Weiland. After the Weiland record was finished, the concept became a burden. It was like a corset, I couldn’t breathe anymore.

So I started The Vision Bleak. Something totally different and straightforward without the boundaries of concept when we started. Of course, I gave it concept again later on [Laughs]. It seems masochistic now. I guess there wasn’t really a regret leaving metal, but I began to miss it. Just taking the electric guitar and making noise every now and then. I still can totally feel that when we play Empyrium concerts. The acoustic songs are so delicate, so fragile, that there is no room for mistakes in playing them live. If you make a mistake in these songs, everyone will hear it. There is so much tension when we play them, it’s almost unbearable. After an Empyrium concert, everyone in the band is just… dead. Much more than when you play a one and a half hour long metal show where you bang your head. In these songs, the level of concentration is so high because there is absolutely no room for mistakes. I think I missed that, just to be a little more loose.

I certainly noticed some of that in Weiland. I think it was in “Waldpoesie”? When you were briefly revisiting the black metal vocals [in a neofolk song].

Yeah. Wait, no, that’s on “Die Schwäne im Schilf” [which follows “Waldpoesie”].

Right, sorry. I apologize.

Oh, it’s fine.

Was that kind of like revisiting something nostalgic?

Yeah, I think black metal was always a very important part of my life (even now) and I never left it. If you were to play a song like “Die Schwäne im Schilf” with blast beats and distorted tremolo picking, it could be a new Sun of the Sleepless song nowadays. It’s really the same at the end of the day, but with a new arrangement. This really fascinated me at this period, especially in Weiland, that the arrangement dictates what kinds of atmospherics you create.

Let’s say you play a melody or a riff, whatever you want to call it. You could play it really slow and silently on a piano and the atmosphere would be totally different than when with a distorted guitar and blast beats. But still, the soul of this melody is the same, and this really fascinated me. We really focused on this with Weiland, and in its three parts. In the first part, the Moor Lands, the Heather, where we put flutes because it sounds “wide.” [Then there is] the piano on the Water chapter, and the plucked strings in the Forest chapter. This was the thought behind that. It’s an intense concept. After we finished, I was a bit tired, but I wanted to do something more… fun.

It was an especially long album, Weiland. I can obviously listen through the whole thing back to back, but I can understand being burnt out afterwards.

I think I was burnt out after I mixed it. It was pre-Pro Tools, so I had to mix it on an analog desk. Mixing a song like “Waldpoesie” on an analog desk with no automation, no faders or anything… it was gruesome!

Well it’s a 13 minute song!

Yeah, it was crazy! After I finished, I thought I needed to “put this book back on the shelf.” You were right, I was burnt out.

You brought up Tenhi, which I thought raised an interesting parallel. The guys in Tenhi also had these very metal backgrounds — one was supposedly in Pohakka, a funeral doom band, and the rest were in Mother Depth, a gothic/doom metal band who is still surprisingly underground. It’s peculiar hearing these people who made these very pivotal neofolk records having these very metal ideas backing them. It speaks to the power of arrangement.

I can totally hear it! I mean, I already knew they were involved with metal, but even without, there is still all that darkness, the tension, and the intensity! It’s very metal. It’s just the arrangement that makes it different from a black metal band, or from a doom band. There are a lot of artists in this genre that are metalheads.

Sure. I can’t think of any individual neofolk group that hasn’t come from that sort of background at this point of time. Unless it’s one of the classic artists who came from punk and industrial music.

Exactly. I just mastered the new Sol Invictus album last week. With them, it’s very obvious he came from that punk background, but you’re right. With the later neofolk bands, I think they are all metal. It’s interesting, I think this is both ends of the spectrum in music, you know?

Yeah.

It’s so interesting that these two genres have so much in common.

Now, twenty years later… you’re living in the city now?

I’m still in the countryside actually! Not so much like I was before, but still in the countryside.

Either way, do you still feel that same kind of isolation now? As a musician?

In a way, yes. Especially now, with the scene, I can feel that I’m kind of never fitting in. A lot of these bands now do the occult, ritual sort of stuff, and I was never drawn to it. It always happened to me that the scene is always at a different point that I am in. For instance, everyone is getting into darkwave and coldwave now, and, yes, I love it, but it’s not news to me, listening to this kind of music! It seems to me like when something is darkwave, it’s enough that it just is darkwave. It doesn’t need to be great darkwave, but I still love it because it’s darkwave. This really bugs me, I don’t know. There’s, of course, still some great stuff, but, not everything is great! I don’t know… Like in metal, there’s Wintersun!

[We both laugh]

God, I couldn’t even listen through that new album.

This is that kind of plastic music which is…[gag]. But in saying like I’m a loner, I feel like I’m not fitting in. Forever, I feel like I don’t fit in because I don’t follow what everyone else is doing. Right now, I think about the new Sun of the Sleepless album, which is obviously a very “back to the 1990s” sound, but without any of this occult ritual stuff, or the satanic whatsoever. I guess there are some bands who are Satanic nowadays which actually communicate the intensity and I appreciate that. But, with so many bands, you see the guys before the gig and they’re… just regular kids, and onstage they do the Satanic ritual… I don’t know. I don’t get it.

It’s not genuine.

There is nothing about it which is genuine. It’s just a copycat of what they see in Watain. This is ridiculous to me. Watain is obviously a band who takes it very seriously and it’s something which comes from their heart. It always seems to be like that with bands in the scene. The people who make it and those who follow it for the outer experience. It’s like fashion, “Wow, it’s cool to look like this.” And there’s nothing true about this, and it’s ridiculous. This is why I don’t feel like I fit in, because I make music which comes from me, which can only come from myself. Of course, I’m inspired by stuff, but I never felt the urge to follow a trend or a scene just to feel more accepted or be more successful.

With the return of Empyrium, and The Turn of the Tides is now three and a half years old, do you feel yourself moving back more toward that metallic sound? I know there were a couple metal-oriented songs on that album which were, like “Days Before the Fall,” but it was more folky, atmospheric… Do you find yourself wanting to make music like Songs of Moors again?

You know, we are already working on new stuff, maybe for a year, on and off. I think it will take another year before we finish an album. I can tell you there are parts that are Songs of Moors inspired, yeah. Of course, it’s not the same because we are in another place nowadays, but there are parts on the metal which are definitely metal. Metal with drums, and bass, and guitars. In general, a return to the more natural sound.

The Turn of the Tides is definitely more Dead Can Dance inspired, inspired by more of Brendan Perry’s solo works. Both me and Thomas [Helm] were really into Brendan Perry’s The Ark. It put its mark on The Turn of the Tides. For the new stuff we are doing, it’s more back to a natural, folky, and also metal sound. Of course, in the way we do it nowadays. It would be disastrous if we tried to copy Songs of Moors now. It won’t work anymore. The arrangements so far are a little more “proggy.” Both me and Thomas have always been fans of this “neo prog rock” stuff from Scandinavia — bands like Landberk [and] the Norwegian band White Willow. It’s always been very inspiring to us, and I think the new stuff we are doing is kind of a bridge between Empyrium and this kind of music, but also older Empyrium, the folky stuff, and the proggy, prog rock stuff.

…

…

How do you feel about these new cassette pressings of your old material? It feels kind of funny that these albums which were never on tape are suddenly out on tape now, twenty years later. I found it funny, as someone who collects tapes.

I love tapes! Some people say they love vinyl, but for me, it’s all about tapes. I used to get vinyl, but I didn’t have a vinyl player, so I’d take it to my older brother’s place and make a cassette out of it. I only had a cassette player. I’m a total tape nerd. I love tape, it’s my format. 90% of the music I love and inspired me, I listened to it on tape, so I love seeing all this music coming out on tape. I just love having a tape in my hands, smelling the tape, it brings back so many memories from my youth. It is funny that nowadays, twenty years later when tape is supposed to be a dead format, that it’s coming back in such a huge style, but with these albums from 1997. I love it.

Sure, I’m a huge tape collector. If I was to turn on the camera, you’d see all my tapes on display behind me.

Nowadays, I have all my tapes somewhere in the cellar because I’m living in a house with my kids and my wife. Not so much room for tapes when kids occupy every centimeter of this house! Back when I was living on my own, it was like a tape library. I even had a number system on them, like, “Wait, we have to listen to tape 223!”

That’s intense! I don’t think I have mine organized now, they’re just kind of… out.

Yeah! I was totally into tape trading back in the 1990s. I got so much stuff back then. Got into non-metal stuff through Loreena McKennitt, Mazzy Star… all through tape trading!

…

Follow Empyrium on Facebook and Bandcamp.

Empyrium’s entire discography is available on CD, LP, and a few cassettes (limited selection for now, but I think the entire discography will eventually end up on that format) from Prophecy Productions (US/EU/ROW).

…