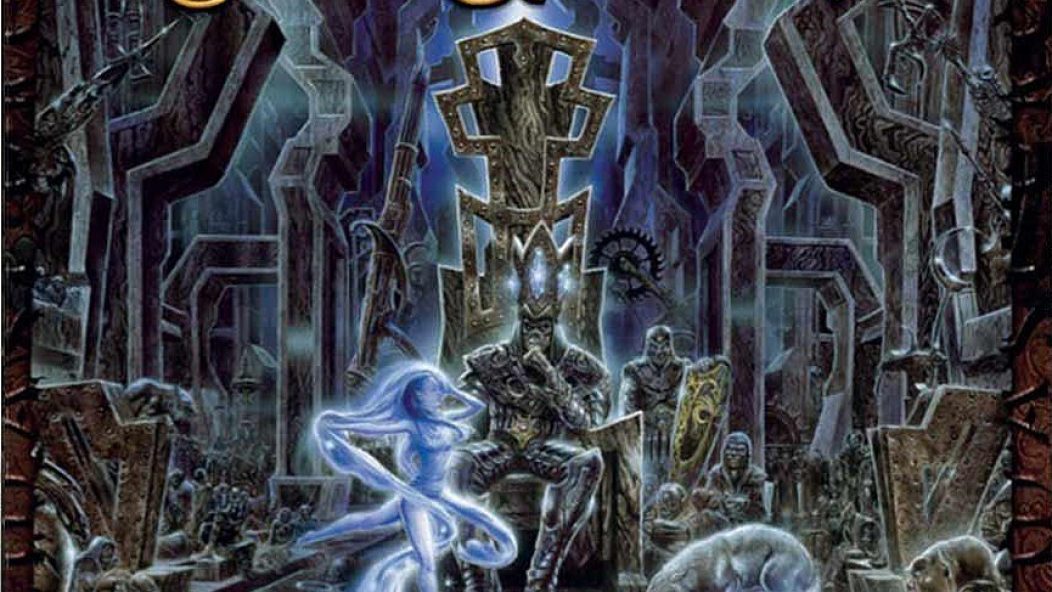

Perfection in Alignment: 20 Years of Blind Guardian's "Nightfall in Middle Earth"

…

Blind Guardian’s seminal progressive power metal record Nightfall in Middle-Earth turns 20 today. There is a general divide in metal fandom between power metal fans and extreme metal fans, one which can be optimistically interpreted as a sign of the breadth of metal in the contemporary world. Blind Guardian manage bridge this divide, one of a few bands the likes of Pharaoh, Manowar, and Helloween who manage to do so, combining elements of thrash metal and traditional heavy metal, as well as integrating harsher raspy and screamed vocals into their sound. Nightfall in Middle-Earth represents the apex of the band’s sound, the moment when all of the pieces they had spent their career up till that point finally were honed to perfection and assembled into an unimpeachable whole. It is a streak they’ve kept alive since, delivering a consistently stellar set of progressive metal records that feel thankfully devoid of trite cliches like aimless song structures, discoherent riff salad, and pseudo-philosophical musings. It isn’t necessary to know the band’s full body of work or broader historical or genre context of the record to enjoy Nightfall, a record that easily, transparently, and endlessly gives up its treasures even on the first listen. But for those of the mind, these details make it that much richer.

…

…

Metal’s ties to progressive rock stretch back to its formation with groups like King Crimson and Black Sabbath. What united these groups was not merely a relative heaviness imparted to them from the hard rock of the late 1960s but also a darker, more fevered take on the psychedelic music of that era as well. Metal has always been, since its inception, about moving beyond; further, about beyondness itself. From the fixation on witches and the Lovecraftian walls of sleep on Black Sabbath’s debut to the fantasy metal epics dotted across Led Zeppelin’s discography to almost every record Judas Priest ever put out, the intertwining of metal and fantasy remained, bound up as one coherent concept.

It is not a surprise that, in the two decades following the decline of most of those early metal bands, a new crop would rise and push this notion further. It was here in the New Wave of British Heavy Metal burst into being, a genre absolutely brimming with holy escapisms both elaborate and troglodytic. Hell, even glam metal hinged itself on fantasy and spiritualist escapism in a way, if albeit in a more KISS-derived hedonistic angle. The major conceptual conceit of thrash was less its musical influence from hardcore punk and more a commitment to a realism, at least of a sort; but even that did not last, and soon its derivatives (power metal, death metal, black metal) found themselves enraptured in spiritualist fantasy once more.

From this soil, Blind Guardian came into being. It’s a necessary set of historical facts to keep handy; far too easily, with a surfeit of cheesy and interminably boring records, do we count out power metal entirely. But doing so hinges on an ahistorical assumption, that the lame and overbearing fantasy antics of a bunch of white European dudes clad in medieval armor on-stage, singing major-key chanteys about elves and shit, can’t be compelling. The turn in modernity toward metallic hardcore and those more cerebral or realist bands seems to confirm this thought. As much as many of those bands are legitimately producing wonderful contemporary metal music, it is hard not to understand where the term “hipster metal” stems from; bands and aesthetics which seem at times deliberately, pointedly either ashamed of the history of metal or simply uninterested in relation to its historical body.

Blind Guardian embraced metal as a whole at the time of their birth. Their first few records featured a strange, but at times powerful mixture of amateurish performances jutted up against heady progressive arrangements, thrash metal syncopation and tension, and traditional heavy metal’s grandiosity and conceptual aims. By the time they recorded Nightfall in Middle-Earth, they had already written a full thrash concept record with Imaginations from the Otherside, released one of the most compelling live metal records of the early 1990s in Tokyo Tales, and tackled Tolkienian subject matter in, well… every record they’d released up to that point. They had stripped their ideas down to basics from their overwrought if joyously ambitious debut and slowly over the course of a decade steadily built them back up again. Their run from Tales from the Twilight World up ’til Imaginations still stands up not just as important historical documents like their first two records, but as great heavy metal records in their own right, cut in a period where what we know as European power metal began to fully differentiate itself both from American power metal (always more burly and thrash-oriented, and at times doomier, too) as much as it was splitting from the broader realm of heavy metal.

…

…

In the wake of Nightfall in Middle-Earth, Blind Guardian found themselves as international heroes, their star ever on the rise even before, but seemingly solidified by, the record. Unlike some bands, it was not because Nightfall was a particularly potent breakthrough record; this was no Master of Puppets, no Number of the Beast, not even a Leviathan. The numbers were good, an improvement from the last record, and the world seemed to be their oyster in the coming years. A Night at the Opera birthed “And Then There Was Silence,” still their magnum opus if one had to pick a single song for the group, and their mightiest performance of progressive metal in a single track. Their follow-up to that record, A Twist in the Myth, the first of their partnership with Nuclear Blast, signalled a comfortable period of progressively greater acclaim and gentle love.

All of which encircles Nightfall in Middle-Earth, the moment where it seemed that everything seemed to align, all forces moving and thrusting as one, penetrating at last the flesh of the world. When listening to the record, even two decades on, it is not really even a riddle to see why. Nightfall in Middle-Earth is Blind Guardian at their most “themselves”; the songs are crystallized down to their most compact form, progressive rock suites dressed in traditional heavy metal guitar harmonies and thrash metal rhythm sections all distilled down to five-minute figures. The interludes, something which would be cheesy and uncomfortable in other hands, here managed to aptly set mood, offer breaths between songs which are sometimes unfathomably dense for their brief lengths, offering continued sonic nuggets even years later.

Nightfall in Middle-Earth was not an accident. Its successes and its strength over time is not some strange and inexplicable alignment of the stars but more the slow, methodical alignment of pieces on the board by a chess player. This is not to say that they knew how successful it would be. Rather, tracking their sonic development from inception to this record, their songwriting style never really changed, but, instead, was patiently honed and adjusted over years of studio and live work and their attentiveness to the emotionally conceptual meta-narrative in timbre, temperature and overarcing mood growing deeper. This was the result of the metaphysical foregrounding of some final fateful X-factor, seemingly lifting their hybrid of thrash, prog and traditional metal above their power metal peers — something which made the genre tag always feel a bit ill-fitting for them even if the connection felt obvious on paper.

Queen’s influence on Blind Guardian’s development as artists can’t be overstated. It’s not just the flowering of frontman Hansi Kürsch from just another “Teutonic thrash guy” into the virtuosic legend he is now, flowing seamlessly from densely layered choirs of his own voice to gorgeous solo vocal tracks to on-the-dime executions of powerful and (most importantly) deeply emotive screamed vocals. Queen also seemed, alongside Metallica, to be an example to Blind Guardian of how to balance their ambitions, the desire to be catchy and memorable and anthemic without necessarily delivering traditionally structured pop songs, and to marry progressive rock arrangement and song form ideals to metal, but with a mind for mood and atmosphere foremost. It was their mindfulness to those smaller details which makes Blind Guardian’s Queen influence less odious than, say, a band like fun., which seemed to shamelessly ape the great British band’s style without fully incorporating it into their own.

Ultimately, like the great debate over the first four Metallica records and Iron Maiden’s hot streak, what makes this the landmark Blind Guardian record in a discography often not celebrated enough by heavy metal’s faithful is that it quite simply has the best songs the band has ever written. This is no knock on the band’s continued work, which has maintained itself at a level which still makes each new record of theirs a momentous and richly pleasurable experience, nor is it to knock their under-sung earlier records, which even at their most warty have more sincere charm and passion than most remember them having. After all, what metal band could pull off a cover of “Mr. Sandman” without it sounding either overly serious or overly jocular? “Blood Tears,” “Mirror Mirror,” “Thorn,” and, undeniably, the mighty title track are not only the greatest songs the band has ever written (save, perhaps, for “And Then There Was Silence”) but are also some of the greatest power metal, progressive metal, or heavy metal songs in the vast catalog of the family tree.

…

…

It’s easy to be effusive in praise for this record. Nightfall is almost uncanny in how well a series of elements could somehow hang together so powerfully. The album manages to span from theatrical interludes to overly dramatic choral attachments to jaunty major-key songs quite literally about elves and shit, all without a whiff of dairy. The reasons for this are anything but mysterious. The thing metal and prog have most in common and why they return to one another so often — why metal often demands an advanced musicianship — is because it is almost wholly concerned with fully conjuring some other world, one which doesn’t exist (or, at least, not yet) and to compel the spirit of the listener to that place. It is a psychic womb, a mirror-doorway to outer realms where the spirit, heart, and hand are reconfigured to alien shapes in the hopes that something is brought back. It is, in that manner, a cosmological exploration of psychonauts who do not always need to be inebriated to tread in the spaces they go. This is what prog strives for at its best and at its worst. This is what metal strives for. It is that ineffable force that ensorcels us that first time we heard “Kashmir,” the first time we heard “Black Sabbath,” the first time we heard “Hallowed Be Thy Name.”

Nightfall in Middle-Earth is a doorway. It breathes out cold air through an icy beard, drops axe and glove on wooden table, grabs your hand, and leads you into the darkness of a world devoid of the Silmarils. On paper, maybe that feels silly. Maybe it feels like it cheaps the experience to see it described that way. But this is an essay, not the record; when the first track starts, you hear a door creak open, and you are taken away again, whether it be on the day of release or 20 years later or, foreseeably, 20 more.

— Langdon Hickman

…

![Bad Omens announce new album CONCRETE JUNGLE [THE OST]](https://www.altpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/17/BadOmens-CROP_2024_JW_0619_Final_V1.jpg)