Black Sabbath's blues

The 40th anniversary of Black Sabbath’s first album has been greeted this year with much fanfare, most of it about how the album birthed a genre. Part of the celebration stems from the fact that metal fans love anniversaries almost as much as they love quibbling about best-of lists. Knowing that putting Pantera, Iron Maiden, or Sabbath on the cover sells copies, metal magazines celebrate more anniversaries than Hallmark shops.

I’m all for celebrating the 40th anniversary of Black Sabbath. It might be the most played album in my entire collection. The album has an earthy, gritty quality missing on Sabbath’s later albums, and it is accessible to listeners that might balk if they heard “Children of the Grave” or “Symptom of the Universe.” Ozzy’s nasal, whining voice is at its best, and the rest of the band performs like this album might be its only ticket out of the Birmingham steel mills (which it was).

My problem with this anniversary is that so many have called it the birth of heavy of metal. Of course, there are elements that support this argument. But when you break down Black Sabbath, you’ll find that the forefathers of metal started their career with a blues album, separated from ’60s greats like Cream and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers only by their ominous, supernatural aesthetic. Only on later albums did they make a tangible leap from the blues idiom to an entirely new form of musical expression. Even then, the blues lingered.

The album starts with “Black Sabbath”, which nearly every critic knows for its prominent use of the diminished fifth – a musical interval forbidden in medieval times. There’s little question that this is the first heavy metal song in terms of sound, lyrical content, and execution. But as soon as Iommi’s guitar fades out, the rest of the album makes a turn back to the blues.

. . .

“The Wizard” (live 2005)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKQ5jhtFypg

. . .

Ozzy’s wailing harmonica on “The Wizard” signals that the onetime Polka Tulk Blues Band was headed to more comfortable turf: the gallows-tinged, Leadbelly-infused blues they played learning their craft in German clubs and bars. Harmonica aficionados will point out that Ozzy is playing a D harmonica in second position on the track. In laymen’s terms, that means Ozzy is bending certain notes so that the harmonica is playing in a different key than intended. This is classic blues harmonica playing known as “cross harp”. The deeply bent two-draw note combination that opens “The Wizard” wouldn’t sound out of place on a Chicago blues track or the Rolling Stones blues number like “Midnight Rambler”, a song about serial killer Albert DeSalvo.

“Behind the Wall of Sleep,” reminds me of Delta blues great Charley Patton in that it’s a slightly upbeat track that somehow suggests menace, even despair. The song seems to indicate that something ominous is about to happen, much like Patton’s “Devil Sent The Rain Blues”, which mourned for a Mississippi Delta ravaged by rains and flooding.

Sabbath was forced to play “Evil Woman” by a record company eager for a hit, so it feels like more of an afterthought. “N.I.B.”, always saddled with the tag “nativity in black”, is unquestionably a blues song in delivery and intent. A somewhat emo Satan is trying to lure his prospective lover with the promises of immortality and “those things you thought unreal”. We can sense Old Scratch’s broken heart throughout.

. . .

“N.I.B.” (live 1970)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZiShfBmb-oA

. . .

Bluesmen have added the devil to love songs with haunting results even before the earliest recorded music. The best example is Delta bluesman Skip James’ “Devil Got My Woman”, which is more pained and haunted than anything in the Sabbath canon. Robert Johnson’s affinity for the diabolical is better known: “Hellhound on My Trail” and “Cross Road Blues” are blues staples.

“Sleeping Village” includes a prominent Jew’s harp and an almost woozy chorus before Iommi’s guitar kicks in. If you listen to the sparse lyrics you can almost imagine them being sung at a backwoods train station or in a country alley.

“Warning” is an extended blues jam originally written by British drummer Aynsley Dunbar, who later played with Frank Zappa. Sabbath played the song much more convincingly and with more authority. Iommi showed his ample blues chops on guitar, and Bill Ward adds fills that, while a bit busy for standard blues, nonetheless work well.

. . .

“Warning” (Aynsley Dunbar original)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3l3c-42huW0

. . .

Taken together, these songs might not get a crowd moving like “Got My Mojo Workin'” or “Born in Chicago.” But the music is about as bluesy as you can get, tinged with the darkness of industrial Britain.

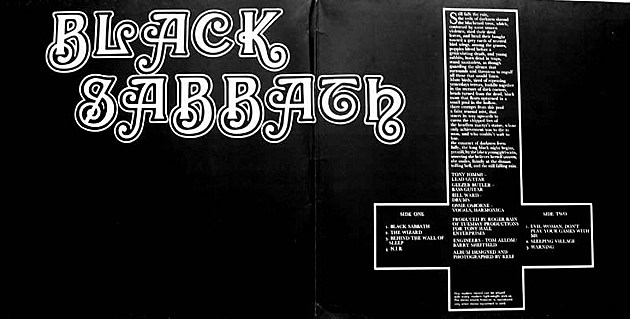

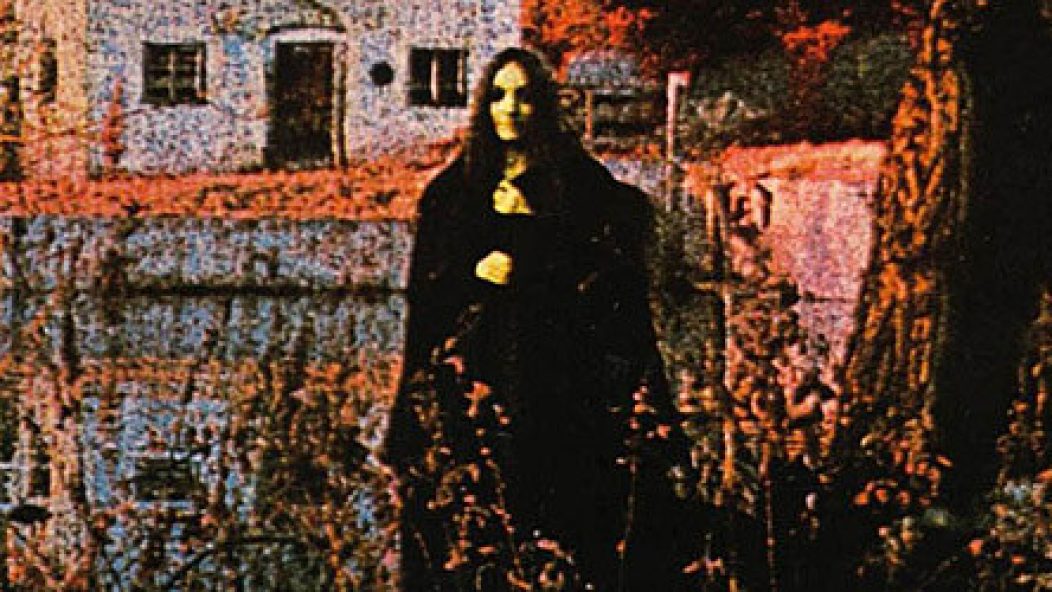

Perhaps the most metal thing about Black Sabbath is the now classic cover and the insert with the inside upside-down cross, which was included without the band’s knowledge. And nothing in metal’s history has ever suggested the otherworldly as much as a simple shot of an unknown woman in black in front of an English steel mill. No one has ever found out who she was.

In his recent autobiography I Am Ozzy (reviewed here), Osbourne endorses the debut album as blues. In short, Ozzy said the band never set out to play heavy metal and only wanted to play a darker form of blues. So instead of celebrating the 40th birthday of metal this year, we should be celebrating yet another reimagining of blues, which is continually denied its proper place in the metal universe. Metal’s official birthday happened just a year later – when Paranoid hit the record racks.