True to Form: Baroness Excels on "Gold & Grey"

…

In just over a decade, Baroness have cinched themselves up as one of the heavy rock bands that really matter in a broader pop-cultural sense. There has been, of course, no shortage of excellent heavy and progressive rock music made in the same timeframe, but the cultural window has since shifted, rendering groups of this type largely outside of the considerations that accepted such other groups as Mastodon. Baroness enunciate their legacy as a seminal band, not unlike the way the Smashing Pumpkins permanently etched themselves into the annals of rock history with Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness — and to do so with a record as superb as Gold & Grey is merely an additional bit of icing on the cake.

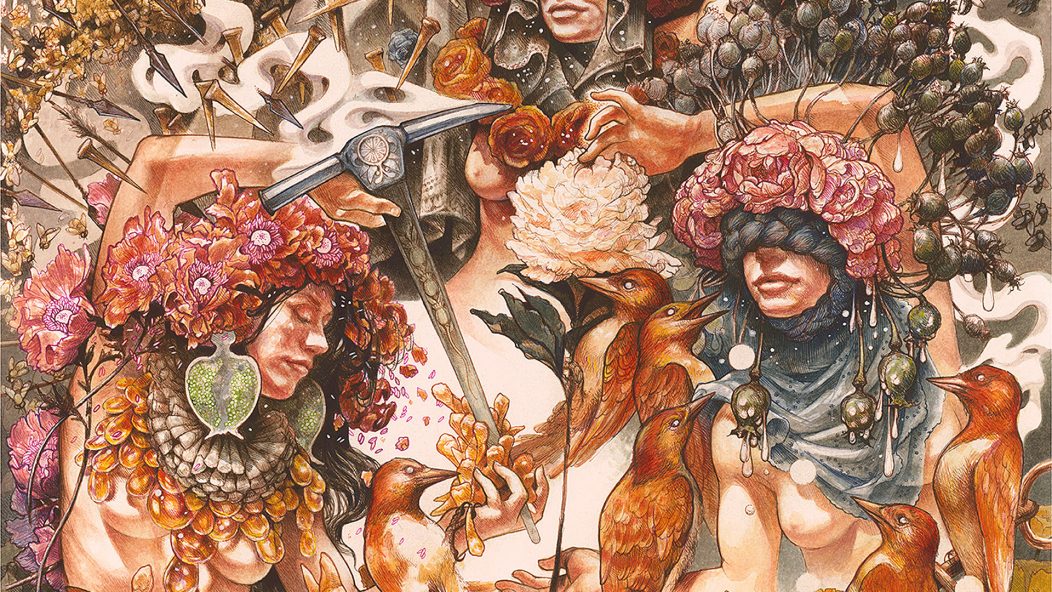

A record as large as Gold & Grey (large not only in terms of the band and the quality of the album itself, but just the sheer girth of the thing) demands a response covering a range of associated topics. First and most banal: yes, it is fine to retitle this record Orange in your personal library if you so choose. Interviews in the time between the release of the first single “Borderlines” and its release have clarified that its working title was as such and (obviously, clearly) influenced the direction of the album art. There’s even a bit of “orange”-ness phenomenologically to boot, which we’ll address in a second. The name change, for better or for worse, was likely meant to sound more like a traditional title than the borderline cliche set of colors they’d been working from before.

This is an understandable reason to change the title but misses, at some level, that phenomenological “orange”-ness which still pervades this album. We did not collectively bat our eyes at the previous color sequence: Red Album felt like a brewing and stewing liminal sun casting first/final rays of light, Blue Record felt like a tangled snarl of weeds cloaking catfish all submersed in Georgia swampy marsh, Yellow & Green felt sunny and verdant, and Purple felt like it emerged screaming out of a hydrocodone haze. Likewise, Gold & Grey feels like it would fit somewhere between Red Album and Yellow & Green by way of Purple, mirroring the sonic structures of Purple but timbrally sitting somewhere nearer the haunt of Red Album and the wide-winged and creatively joyous span of songwriting demonstrated on Yellow & Green.

On paper, Gold & Greymay not be a proper double album, but it certainly has the internal structure of one. This largely comes from its superlative size: 17 tracks over an hour’s duration. While on paper this may not feel necessarily long enough to constitute a double album, remember that Yellow & Green was only 75 minutes, short enough to fit onto a single disc, with the average Baroness record outside of these two clocking in at just under 45 minutes. This sense of doubled-ness does the name change a favor; there is, whether intentionally or not, discrete Gold and Grey portions, signaled by the timbrel change from driving, noisy heavy alt rock tunes to more brooding and atmospheric fare, like the light and color was sucked out of it. However, despite the size of the record compared to their standard lengths, they manage to pace this affair far better than their previous double album, with Gold & Grey having a clear emotional arc aligning each of the tracks.

That is not to say that the album will not be a formidable challenge to newcomers. Unlike Blue Record, which was at once (still) their best sequenced work, playing out more like a grand Southern Gothic novel in a 45-minute span, Gold & Grey has substantial differentiation between its tracks, more so than the band has shown before. Where on Blue Record the interludes and even full songs included repeating melodic and rhythmic motifs to tie the album together, Gold & Grey is a linear affair, abandoning each concept as the track number changes over. What’s left instead for Baroness is the trickier task of making sure where one track leaves off emotionally can be properly expounded or else satisfactorily challenged by the following track, a task they thankfully do accomplish. It creates a subtler and ultimately richer album than Blue Record but does noticeably rob the album of the same immediacy. It will likely take a handful of listens before the average listener can make it all the way through and still feel like they are actively following the music rather than getting mentally fatigued by the number of ideas.

Speaking of which, we see Baroness not only at their most adventurous in terms of new ideas but most conclusive in terms of cataloging old ideas. There are moments of heaviness that rival (but admittedly do not best) the early EPs: sweeping and complex progressive metal numbers that hearken to their first two albums, melodically driven alt-rock salvaging the adventurous but largely unsuccessful attempts on Yellow & Green, plus the new-school standard of noisy, heavy, weird-out rockers from the Purple era. Baroness seem consciously aware that this is the end of a cycle, albeit one they likely didn’t fully understand until they found themselves near its conclusion.

And yet, despite this sense of encyclopedic span, marking King Crimson-esque mathy prog on one interlude and noise rock on another — Smashing Pumpkins grandeur on one song and then accessible and warm pop rock on another — Baroness do not feel like they are attempting to impress anyone but themselves. Yellow & Green was their most ambitious but least inspired while Purple felt like a band fully loaded with ideas they were chomping at the bit to employ; with new guitarist Gina Gleason joining their ranks, it seems like the final barrier was removed, and Baizley’s group can finally do anything and everything under the sun.

…

…

There is a narrative regarding the band that has to be addressed to properly internalize Gold & Grey. Baroness may have emerged from the same mathy sludge metal origins as the early days of Kylesa and Mastodon, but they were misapprehended in the same manner as those other bands, viewed by fans and critics alike as primarily heavy as fuck instead of progressive. But while Mastodon and Kylesa pursued progressive ends without internal qualm from two separate directions — Mastodon shooting for classic prog and Kylesa for dense psych rock jamming — Baroness wanted something subtler. So was born the borderline-symphonic approach to Southern rock and heavy metal found on their first two albums; but this too saw the band with raised ire, with Baizley decrying Yes as bullshit and The Jesus Lizard as closer in his mind to what the band was trying to achieve with mathy progressive ideas in metal/rock contexts.

It wasn’t a surprise that the follow-up to Blue Record would err more to discernible rock forms and less to overtly prog ones, achieving progressive space more in arrangement and timbre than in stacking the record with songs that eschewed verse-chorus writing. Then came the horrible van accident, one that certainly shifted whatever direction the band would have naturally grown in as they lost both their bassist and, worse, their drummer, a founding member and a player that had a deep foundational influence on how the group approached rhythm and structure. Purple then was not just a sign of Baizley’s return to functional health — the existential weight of the crash and the long-tail of medical trauma perhaps shifting the sonic direction of the band — but also the integration of an entirely new rhythm section, one more versed in noise rock and punk and jazz than in heavy metal and prog. Gold & Grey should be seen, then, with its replacement of the sole remaining member of the band from before Purple, not necessarily the sixth Baroness studio album but more as the second of this particular line-up; as much as it gestures back, this is an affect you have to dig for within a record that seems substantially more comfortable moving forward from its immediate predecessor than any of the others before it.

Which leaves Gold & Grey a substantially more subtle and mature record than either Blue Record or Purple, the group’s two prior high points. Blue Record felt more novelistic and cohesive than Purple but was almost emotionally crass in terms of how grandiloquent and, in spite of Baizley’s protests, Yes-like in its development of themes and moods; Purple is the group mastering the art of being a rock band first and foremost, allowing them to incorporate prog, psych, and noise concepts at will, not to mention an encyclopedic knowledge of all the goodies of non-mainstream rock music. Gold & Grey is a hybrid of these two approaches, giving itself a superstructure that reads more as a single cohesive statement made up of 17 seemingly unrelated shards, a greater mosaic that only reveals itself in assemblage and not at all in isolated individual components.

You may feel you understand the record from the singles, but that would be incomplete: moments that catch the ear suddenly don’t in the greater context of the album as a whole, while other subtler moments suddenly feel like more substantial emotional comments on what came before. And yet it contains songs, great and anthemic songs, some of the very best of the band’s career. Baizley, Gleason, Thomson, and Jost seem to effervesce joy even when singing about sorrow, and the whole album crackles with a fierce and seemingly limitless creative verve, one we’ve needed to hear made explicit in rock music for quite a while. The album feels honest-to-god adventurous for a change, instead of day-in, day-out genre pastiche and ripoffs. The record is less grand but only because its gestures are less crass, patient not as a code-word as boring but instead sure of the fact that they can move the whole ship with little touches and still make the whole thing rattle and shake the way a good rock record should.

This in turn makes the elephant in the room grow bigger: the production, overseen by David Fridmann, clips horribly across its span, rendering stretches almost unlistenable in their noisiness… not in the noise rock sense, where the wailing walls of distortion and feedback snarl together into formidable tidal motions. Those moments spot this record too, but the noise Fridmann adds comes from maxed-out waveforms absolutely crushing not just the guitars that generate it but also all sonic nuance underneath. It’s an issue that doesn’t resolve itself with good headphones or sound systems either (the same stretches tested on my high-end stereo versus earbuds produced the same artificially noisy unlistenable periods). This is, mind you, something from the producer and not the band. We know this because the precise issue plagued tracks on Purple (the only negative of that album too) while being noticeably absent from live performances of said tracks which then adopt a good bit more air and warmth to them. This is frustrating not only because of how it mangles and potentially ruins this record for some, but also because Fridmann has an undeniably great resume behind him, having worked with groups like Flaming Lips, Tame Impala, and even the recent quite-good MGMT album over the course of his career, not to mention The Great Destroyer, Low’s greatest achievement.

It’s easy to see why Baroness would want to work with him, but it seems like a group this heavy is just a bit out of his command, especially compared to the superlative work John Congleton did on Blue Record and Yellow & Green; hell, for all its faults of often uneventful songs, Yellow & Green sounded absolutely beautiful, making the change-up make little sense in that respect.

Overall, the issues of intense clipping don’t necessarily ruin Gold & Grey, but they do place a noticeable barrier between the absolutely great songs and immediate rich satisfaction. Without those issues, Gold & Grey would undoubtedly be the greatest record of the group’s discography. It is a development in all senses not just on Purple‘s approach to more immediate heavy progressive rock but also on their mastery of the album as a cohesive statement within rock music. The issues of the mix, however, are substantial, and that combined with the length and subtlety of the album produce a much more challenging listen than fans of the group will have faced before. For some, I would venture, it will prove too much, and we will hear much about the faultiness of this record as overlong and mangled in a manner not unlike the infamous Death Magnetic. However, this feels overly damning; the issues of clipping diminish in the affect the more you listen, thankfully only reaching its apex when all four band members are really roaring, which on an album spotted with so many subtler songs and moments is less often than you might think. Eventually, the ear becomes better at parsing structure and substance through the noise, and the problem lessens as a result.

These issues, however, will not sink the record ultimately. Gold & Grey is destined to cinch itself up against all of the other records of the band’s esteemed career as yet another reason why the group has become a seminal one: one that already is among the all-time greats and seems destined to be a permanent fixture on any decent list of quality rock, metal, or prog bands. Further, it will undoubtedly (rightly) appear in many year-end and decade-end lists, likely edging out its own sibling Purple for Baroness’s representation on such lists.

Cherish it. Music this good doesn’t come around every day.

…

…

Gold & Grey released last Friday via Abraxan Hymns.

…

Support Invisible Oranges on Patreon and check out our merch.

…