Deep Into the Brousse: Lugubrum's "Albino de Congo" Ten Years Later

…

Metal loves a good mystery. Ulver’s infamous car photo spawned one which lasted for twenty years. Niklas Kvarforth faked suicide. Silencer’s Nattramn convinced the public he attacked a small child with an axe. Countless artists live normal lives under pure anonymity, entirely separate from the art they make. There is something to be said about the way mystique and metal, black metal in particular, interact. If black metal is the music of atmosphere, then the mystique of the artist and the stories which surround them makes it twofold, interdisciplinary.

Long-standing “Brown Metal,” as coined by Zero Tolerance’s Nathan T Birk in 2003, band Lugubrum are masters of the mystery and story art so integral to black metal. According to the band’s own lore, Lugubrum is, or rather was at this point, a group of Flemish farmers who picked up the art of black metal after a long, drunken night — a practice which has followed their creative process to this day — giving birth to what they called “Boersk blek metle,” or, translated from Flemish, “farmer black metal.” Given the band’s aesthetic, with similarly grotesque artwork by mastermind Midgaars, Lugubrum’s first era follows a homologous sound aesthetic; reminiscent of a Pieter Bruegel the Elder painting, their music is rife with the (often scatological) disgust and strife of peasant life. The music was a strange, idiosyncratic melange of jazz idioms, deconstructed rock-esque chord structures, folk interjections, and broken time signatures, all of which fall under an umbrella of terms people use such as “Lugubrumesque” or “Lugubrumian.”

As the band grew, their vision clarified, but the execution grew further toward the avant-garde. Should each album be considered its own shade of brown, the color palette found toward Lugubrum’s fifteenth year was obscured, and 2007’s De Ware Hond found the band at an equally hard-to-define point in their career. However incredible this particular writer (and many others) feel that album’s free-form abstraction is, Lugubrum was at an impasse. Something needed to change. At the risk of sounding rather comedic (though comedy is an important part of the Lugubrum experience): what do many artists do when at some sort of creative impasse? They go on vacation!

The black metal world was more than confused when Lugubrum announced their imminent trip to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in late 2007 — even members of Lugubrum were. This was no adventure into the Fjords nor an expedition into the Black Forest — going to Africa was unprecedented, completely separate from the historic locational contexts which defined “black metal.” Lugubrum escaped in search of inspiration and looking for the magic of change. From the depths of the jungle, these Belgians returned with their later-career-defining Albino de Congo, which enters its tenth year today.

Does this album sound particularly like Africa? From an ethnomusicological standpoint… at times, maybe. The thumb piano, or kalimba, certainly helps paint a picture, as well as a greater feeling of “humidity” which surrounds the songs. However, at least for the most part, Albino de Congo sets the stage for a new Lugubrum — a new wave of creativity brought forth by a new lineup, featuring Paragon Impure bassist Noctiz’s melodic acrobatics in tow.

When listening to the music itself, there is a strong return of Lugubrum’s short, bizarre ideas; even from the bouncing opening seconds of “Kadurha,” it is obvious Lugubrum is at their most singular, their most “Lugubrumesque.” Ideas feel more progressive and strange, execution is drunk and sloppy, but there is a greater expanse of atmosphere and sound which hadn’t been explored before this. Consider the lengthy, psychedelic passages in “Kurlerha Omugongo” or the meditative haze of “Mushole” — Lugubrum spent their career distancing themselves from black metal’s traditional fare, but there was little precedent for such blatant, Summery 1970s kaleidoscopic sound. Such adventuring and self-discovery could only really come from the experiences of rural Flemish farmers in a completely alien portion of the planet. This creativity set the stage for the band’s further works, in which they continued to destroy their musical ideals, rebuild, and begin the cycle all over again. Such is Lugubrum.

Of course, “Flemish farmers go to the Democratic Republic of the Congo” is much more than a story or an album concept. There is, naturally, a greater subtext in tow. The band’s home country of Belgium and the now-Democratic Republic of the Congo are inextricably linked thorugh King Leopold II’s acquisition and colonizing of the Congo in 1906. Leopold II committed countless atrocities as part of the “Rubber Campaigns,” or “Red Rubber,” in which the Congolese were essentially enslaved as part of a greater rubber harvest. Those who did not meet quotas were mutilated, dismembered, or killed, depending on the “severity” of their actions or the severity of the disciplinarian. According to Midgaars (below), those who were not killed contracted the fatal, insect-borne Sleeping Sickness (African trypanosomiasis), which still infects thousands each year. In Leopold’s (and Belgium’s) wake, the Congo was left in turmoil which can still be felt over a century later.

This theme adds an unexpected and much deeper context to the music. Much like the disgust of Flemish serf life Lugubrum portrays in their farming days, Albino de Congo carries an internal disgust, the guilt of a nation placed within the confines of a single album. On the surface Albino de Congo seems silly, a black metal band going on a seemingly random trip to Africa to “find themselves and record a new album,” but beneath, there is the sinister nature of a group of Belgian adults seeing the squalor and instability left as consequences of their recent ancestors. This is something which shapes the world — a wealthy, or “developed” (by Western standards) nation finds a new source of revenue in a developing nation and exploits it. This is returned as the cycle continues. Colonialism, capitalism, Midgaars, himself, believes these are the scourges of the Earth and conceptually portrays his inner angst in the best way he is able. Soon the Earth will be ravaged by capitalist exploitation.

Which takes everything back to mystery. Looming over Albino de Congo, the question remains: did Lugubrum actually go to Africa? The answer itself is unclear. Sure, there is the connection to Belgium’s past and the band’s purely conceptual, classical portrayal of history, for which Midgaars possesses a vast and thoughtful knowledge. However, there is, as Midgaars states below, the practice of Belgian people actually visiting the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the band even cites a specific studio at which they recorded this album. It could very well have happened. There is this mysterious duality of possibility which completely marrs a simple “yes, they did” or “no, they didn’t” answer without empirical proof or denial; both could potentially be viable. In this case, things are a little more complex than the black and white of those options. Given the concept of the album and its moral subtext, is the implication of the band not going even that big of a deal? And who knows, this really could be “[…]the best Belgian Black Metal album ever recorded in Congo,” as stated by Midgaars’s now-defunct Old Gray Hair label. If not, it makes for a good story. Why not perpetuate lore? Embrace the surreal every once in a while. Such is Lugubrum, where everything is Lugubrumesque.

I ask that all of you take a moment to suspend belief and read a brief interview (we were cursed by the demon of time) I conducted with Midgaars, as we discuss the band’s trip to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, their experiences there, and, ultimately, what it all means.

Albino de Congo can be purchased from Aphelion Productions.

…

…

Now that ten years have passed since you documented your meditations on Lugubrum’s legendary “trip to Africa,” what is revisiting Albino de Congo like, if you have at all?

It’s still one of my favourite Lugubrum albums. For one thing, it’s not too long. I don’t like listening to long albums by us. Some of them I never listen to anymore for that reason. And it features my old friend Slosse, who passed away less than a year after the recordings. It’s always nice to hear his voice again. And I like that whole damp, sweltering atmosphere that runs through it like a tropical fever.

What drove Lugubrum to adventure off to the formerly-Belgian ruled Democratic Republic of Congo? Surely this was a big change for a band of farmers (Noctiz excluded, as he had just joined).

A lot of Belgians who left for Congo were farmers, in fact the government encouraged agricultural emigration; the “Service d’ Agriculture” was founded in 1910 with this aim. The idea was to make the colony self sufficient and thriving so the state didn’t have to invest in it. Ever since I came to Belgium in 1988, I had been hearing stories about the Congo from friends, school teachers, people I met in bars… some of them had been born there. So, it didn’t take long before these images started to surface in my artistic outbursts. I think the Lovendegem soil was getting exhausted. Sure, it raised some eyebrows within the band when I announced we were actually going there, it’s not exactly standard black metal, or standard anything… I guess that’s exactly what attracted Noctiz to join the band.

Obviously you left with new influences (a deeper rhythmic sense, wider palette of psychedelic sound, and some new instruments), but how were you able to incorporate this into the unique Lugubrum sound without losing identity?

I think the Lugubrum identity is built on exploration, so the journey into the brousse (trans. “bush,” or jungle) becomes a search within myself, along overgrown paths until I get lost. Maybe the goal is to lose identity, only to regain it time after time.

When it comes to losing and regaining the band’s identity, the actual approach to the album must have been impetuous and peculiar. When it was time to write and record Albino de Congo, was there anything you wanted to achieve other than the portrayal of events? That is to say, was there anything explicitly musical you set out to do?

As you know, the De Ware Hond line up fell apart, and with it the opportunity of another freeform album. So it was back to basics; from the start I kind of envisaged a more introvert feel, like an insect observing from a leaf. The only direction I was sure of was to avoid any paths we had taken before. In the distance I could hear the sound of chainsaws ripping through wet wood, faint Pygmee rhythms, and jungle birds chattering. When I started writing the songs, Barditus, Svein and myself were mysteriously struck by different illnesses. Barditus even had to stop drinking for good, Albino de Congo was to be his first sober album.

Then we had to build a new rehearsal studio from scratch. It felt like we were cursed before we had even set foot in the Congo. It was one of those times I thought we were finished as a band, but somehow ideas materialised and even before I was fully recovered we were looking for a new bass player. Noctiz joining was indeed bolt of lightning, working himself into the old repertoire and contributing to the new songs with aplomb. That’s what I mean with losing everything. I wouldn’t call the creative process impetuous, it was controlled and literally healing — the flow was organic, like a boat trip on the river Congo. We just let that huge, brown river take us downstream…

The Bantu-dialectic languages found in the song titles (Chichewa, Shona, and Zulu) show you did more traveling in the area surrounding the Congo. What was your trajectory like?

Most of our time was spent at Bodo studio, Kinshasa, but we made a short sightseeing trip to the Bushi region in the eastern part of the DRC (South Kivu province). We stayed with a farmer who showed us how to cure livestock disease with traditional medicine. He also brewed his own alcohol with banana peels which gave us bad diarrhea (mushole).

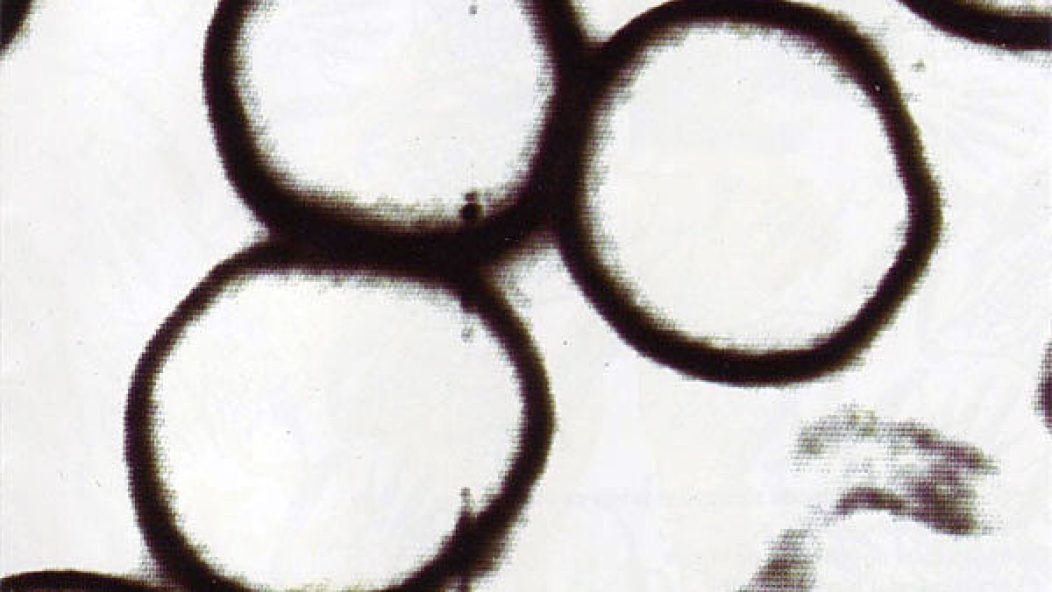

The album cover itself is centered around a photo of what I believe to be the Ebola virus. How does this play into the Albino de Congo theme?

This is not Ebola, but in fact Sleeping Sickness. African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic disease of humans and other animals. It is caused by protozoa of the species Trypanosoma brucei, usually transmitted by the bite of an infected tsetse fly and are most common in rural areas.

The rubber campaigns of Leopold II and the second World War took heavy tolls from the Congolese; deportation and forced labour resulted in millions of deaths. To meet the rubber quota labourers were forced to go deeper into the forests, weakened and malnourished, where they fell prey to the tsetse fly. After the war, some missions recorded 20% infected people, while the disease was believed to be conquered a few years before. An estimated 11,000 people are currently infected with 2,800 new infections in 2015. More than 80% of these cases are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Seeing all of these people in such a way must have left a deeper mark on the album itself. As there is a bit of a language barrier on my behalf (and a lack of published lyrics), was there any way you tried to portray this sickness on the album outside of the artwork itself?

The disease is mentioned in the (French) [Editor’s Note: French is one of the main spoken languages in the DRC.] lyrics;

Sleeping sick grandmothers

of white negroes*

held hostage

carry our bronze horses

*[Editor’s Note: albino people in rural parts of the DRC, the actual “albinos de congo,” are kidnapped and subject to sacrifice and/or dismemberment as part of magical rites. It is believed albino people possess magical qualities.]

This album and concept obviously goes beyond the band’s trip to Africa and means more than the story it weaves. I was wondering if you could go deeper into the idea of Belgian colonialism in the now-Democratic Republic of the Congo and how it resonates within you and the album.

The story of Belgian Congo is as absurd and surreal as the country of Belgium itself.

It started of course with King Leopold II, who, under pretense of founding a humanitarian organization aimed at the abolition of slavery in Central Africa, laid claim to the Congo — an area 80 times the size of Belgium — with help from the explorer Henry Morton Stanley. At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, the colonial nations of Europe and the US authorised his claim by committing the “Congo Free State” to improving the lives of the native inhabitants (!).

The pretext of bringing civilization to native peoples is inseparable from colonization throughout history, and, at best, a delusion inspired by religion. It was usually a license to rob a country from its riches or simply steal the land itself.

Leopold never visited Congo, but extracted a vast fortune from it, initially by the collection of ivory, and, after a rise in the price of rubber in the 1890s, by forced labour from the native population to harvest and process rubber. Under his regime, an estimated 10 million Congolese people died from abuse, starvation, disease, or forced deportation.

International opposition and criticism caused the Belgian parliament to compel the King to cede the Congo Free State to Belgium in 1908, for the considerable sum of 215.5 million Francs. The Congo Free State was transformed into a Belgian colony known as the Belgian Congo under parliamentary control, until independence in 1960. Soon, the country was facing civil war. Its first leader, the Congolese nationalist and pro-Soviet Lumumba was killed in January 1961 and then came a looting dictator who was the country’s image of Leopold II: Mobutu.

The aftermath of colonization: bad government, bad economic management, and outright corruption are ills which bedevil many African countries today, and can, for a large part, directly be attributed to this historical past. Congo’s biggest problem is its abundance of natural resources, be it rubber, copper, gold, uranium or coltan, the world needs it and the region will never know peace because of it. Our human history is defined by colonialism, so it’s a story that should be familiar to everyone and one that continues, in the shape of Capitalist Globalization.

…

Follow Lugubrum on Facebook.

…