African Metal #6: Zambia and Zimbabwe

…

ZAMBIA

What happens if a nation combines independence from colonial rule, mass migration to a rapidly industrialized mining region, and the growing popularity of Western rock? Throw in a government mandated quota for domestic music on the radio, and you’ll get Zamrock — Zambia’s answer to 1970s psychedelia and heavy jams. It was an eclectic affair, hybridizing everything from Jimi Hendrix to James Brown with liberal doses of Latin and, of course, traditional African sounds. Unsurprisingly enough, there were also a daring few who cranked their amps higher and struck chords harder. The result was psyched-out proto-metal that wouldn’t be altogether out of place alongside Deep Purple and Black Sabbath. A sort of Funk Sabbath, if you will.

…

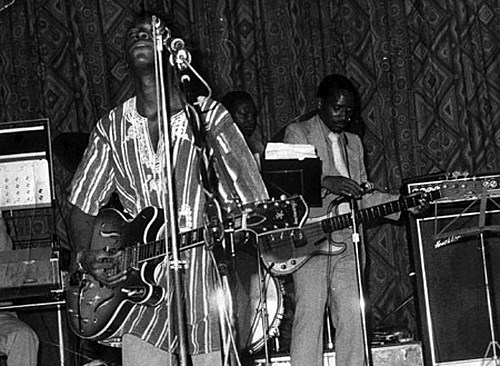

Ngozi Family

…

Perhaps it was an expression of frustration at the economic recession during the 1973-1974 oil crisis. Maybe it was a simple desire to play wild music among a newborn nation’s first urban generations. Either way, the likes of Witch (an acronym for We Intend To Cause Havoc), the Ngozi Family, and Amanaz (also an acronym, Ask Me About Nice Artistes in Zambia) were early — and almost forgotten — precursors to heavy music on the African continent.

…

Witch

…

Speaking over a particularly bad Skype-to-mobile connection between NYC and rural Zambia (Optimum wifi router gets the blame here), Keith Kabwe, former Zamrock star and Amanaz frontman, kindly retraces his rock’n’roll days of old. “We use to, at that time, get into so many other things; we smoked, we drank. But when it came to the music we went crazy,” he admits, somewhat reluctantly, of his rockstar past and the infamous stage performances, where he would dress in a skeleton costume.

…

Amanaz

…

“Maybe I could go on stage, and my friends were playing an instrumental, and there were all the guys and girls dancing and laughing, but when the time comes it was something else, you begin to change. You want to go on stage with a different style, not what your friends are doing. You want to do something different so that you can make people go crazy.”

And people did go crazy. Zamrock, in Zambia at least, was a national sensation. But it didn’t last long. Like most Afro-rock from Nigeria to South Africa, the rolling tides of continental unrest consumed the burgeoning scenes.

Keith attributes the rise of disco (even Witch, the Zamrock greats, delved into the world of synthesizers) to Zamrock’s decline, as well as “aspiring musicians [flocking] into the country. There were so many, and they were playing the rumba music and we were playing the rock music — two different kinds of music. Audiences wanted to listen to something different from another country.”

Forty years later, Keith is now a pastor with a growing congregation. It’s a fittingly drastic conclusion to a long life as a freedom fighter, miner, rockstar, and typewriter salesman. “From a musician…to a man of God,” he ponders. “The difference now is that I am playing God’s music and I have trained boys and girls who are singing now at church; we have small instruments and are using keyboards, but we are still looking for the drums and some good amplifiers.”

“At the moment I’m looking at what we used to do,” he continues. “I’m on the other side, I’m on the flip side. This time I will do things better than I used to do them.”

But for all the personal and social change, Zamrock is still remembered — even if many of its original stars have sadly passed away. “There are some remnants of musicians who remember, although most of the friends and many other musicians who were active at that time…most of them have packed up. They are no longer in existence, and the new boys and girls who have come up, they still remember where the music comes from, they still recall and they still give respect.”

Fast-forward to the 20-teen decade. Zambia is regionally stable, though not without its economic difficulties. Neighboring Botswana is stirring the global metal scene with its leather-clad headbangers — as is much of the African continent. Yet, contrary to the revived interest in Zamrock (Now Again Records have re-released various Zamrock records), it would seem that there is no direct correlation between Zamrock and African metal. Nevertheless, link or no link, at least one group from the national capital, Lusaka, are attempting to reignite Zambia’s heavy-music tradition with a notably contemporary, and culturally contrary approach.

Wrecking Tanganyika (named after the iconic lake that pokes into the nation’s northeastern borders with Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo) perform a distinctive and self-styled “African Death Art”. Driven by African rhythms and curious composition that use MIDI instruments, the result is a somewhat innovative death-meets-Afro-electro-noise.

…

Wrecking Tanganyika

…

Born out of a distaste for their generation’s musical preferences, Wrecking Tanganyika put their mission in their own words: “Our hate for the African type of pop, R&B, and rap, we started listening to metal in schools and soon formed this band to encourage others to do so as well!”

Not that such encouragement assures smooth sailing. As seen in previous articles, the advocacy and practice of heavy metal is frequently hindered by a prevalence of oppositional religious beliefs. In stark contrast to Keith Kabwe’s eventual religious path, Wrecking Tanganyika report familiar difficulties with religious opinion: “It really is hard. Religion is a dire front in Africa, and metal being known for its ritualistic and Satan-worshipping nature has really brought down our popularity. Then again, we’ve been known for being very optimistic. Even [religion] hasn’t stopped us.”

…

ZIMBABWE

Due south, Zimbabwe has also entered the halls of African metal. Zambia and Zimbabwe have long been historically linked, from their colonial years as North and South Rhodesia to apartheid and the Rhodesian war destabilizing the region, the fallout from both affecting the longevity of Zamrock. Even back in the 1970s, Amanaz made a brief venture to Zimbabwe, albeit achieving little success. (“We went to Zimbabwe. Not very [popular] because it was only once,” says Keith Kabwe when asked about Zamrock’s international appeal.) In recent years, Zimbabwe, formerly the jewel of Africa, has come to be defined in mainstream headlines by hundred-million-dollar banknotes, hasty land reformation policies, and election violence. But for now, let’s forget all that and focus on something positive — Harare’s Dividing The Element, one of Zimbabwe’s few defiant forces in the rise of African metal.

…

Dividing The Element

…

Striving to perform crushing riffs against all odds after forming in 2012, they promptly recorded their debut EP, Revolution Among Oppression. Vocalist Chris Van initially met guitarist Sherlic White via a Facebook page for rock and metal fans in Zimbabwe, and after quickly establishing a rapport, they were joined by Alek Zec on drums and Archie Chikoti on bass. With their shared frustration at playing in cover bands, Dividing The Element quickly became an outlet for their love of metal and ultimately a catalyst for the national scene. “There are a bunch of metalheads here from all ages and races, but no one knows anybody else. We then figured that besides allowing us to write and play music in a form that we actually want to, forming a local metal band was one of the best ways to start building the foundations of such a scene. Basically, we wanted to hype people up in order to kickstart the gathering of the masses.”

This scattered and sparse metal “scene” is also the main influence behind the EP’s title theme. Avoiding any details as regards to political commentary within the lyrics (“Unfortunately I won’t go into great length about the underlying messages of the songs, as Zimbabwe does not currently have anything akin to the First Amendment,”) Van tactfully explains that the Revolution Among Oppression motif makes greater reference to “something that would give the impression of referring to the state of the country, but which was actually referring to a metal band emerging in Zimbabwe, no matter how unlikely the odds. Basically, ‘Fuck you, here we are.’”

Thunderous and aggressive like a charging rhino, Revolution… is itself a regional jewel of deathcore, recorded by fellow Harare musician Gary Stautmeister, whose own Nuclear Winter project offers some skillfully composed industrial melodeath.

…

Nuclear Winter

…

As for future plans, Dividing The Element are experiencing something of a hiatus following Sherlic’s departure to study in South Africa. Rehearsals continue for a new guitarist, and following a previous attempt, hopes still remain to bring in Botswana’s death metal bruisers, Wrust, to help bolster the Harare scene with a live performance. Hindered by red tape (the eternal curse for any band seeking international movement), as well as by the announcement of national elections, the show was put on the backburner. “That was intended to be our big launch, as well as the release of Wrust’s new album Intellectual Metamorphosis,” laments Van. But all is not lost: “The key word here being ‘postponed’, as we definitely still want to try and pull this off! I am a big fan of Wrust and I believe that they would go down well here. This time round, we know what we are facing!”

Thanks to Chris. A. Smith and Now Again Records.

…