A guide to writing about music, pt. 3: Writing

. . .

This is the third part of a three-part series on writing about music.

Part one discussed the necessity of reading in order to improve one’s writing.

Part two discussed how to have interesting things to say about music.

This part discusses how to say those things.

In other words, this is about writing. Working with words is not glamorous. It is mechanical: produce, organize, edit. You are transcribing thoughts from your mind. You want to do this as accurately as possible. Think again of the transparent vessel metaphor. Words should lay bare thoughts, not obscure them. Here are 10 tips to help yours do so.

. . .

10 TIPS FOR WRITING ABOUT MUSIC

. . .

10. Do not write until you know what you will say.

People who think out loud are annoying. Don’t be like that on paper. Purge ellipses from your writing.

Writing is a hostile mission. The mission is to get people to listen to you. It is especially hostile on the Internet, where people use any excuse to click away. The average time per visit on this site is barely over two minutes – and that’s with an audience that considers itself thoughtful.

If you perform to thousands, and you know they’ll all leave after two minutes, you can’t afford to think out loud. You must hit hard and fast.

. . .

9. Organize what you will say by paragraphs.

How do you hit hard and fast? You form a plan of attack. The easiest way to do so is by paragraph. Each paragraph should express a single thought. Together in sequence, the paragraphs form an argument.

Take, for example, a review of a fictional band called Pounder. (Thanks to Matt Harvey for the name.)

Pounder’s debut is the best ’80s metal album not made in the ’80s.

It captures the forward-thinking sensibility of ’80s metal at the time.

It’s also a throwback to ’80s lyrical values – which makes it timeless.

Finally, it flat-out rocks.

If each of those sentences begins a paragraph, the rest of the paragraphs practically write themselves. You need only supply supporting examples and analysis.

Note that these sentences form a logical line. A reader could get a good overview from those sentences alone. You are setting out a roadmap for the reader. This is important when you have mere minutes to make your point. A directed reader is an engaged reader.

. . .

8. Avoid the passive voice.

“Drums were played, guitars were strummed, beer was drunk”: the passive voice is weak because it lacks actors. The strongest writing is that of action: subject-verb-object, actor-action-object. Boom-boom-boom. Don’t stop hitting.

The passive voice is also politically odious. Politicians use it to avoid taking responsibility. See Ronald Reagan: “Mistakes were made”. Don’t be like Reagan.

. . .

7. Minimize the use of adjectives and adverbs.

Stephen King makes this point in his book On Writing. Heeding it is probably the biggest reason why my writing looks how it does.

Adjectives and adverbs are like frosting. No one wants to eat a cake that’s all frosting. Cut the fluff, and hit with nouns and verbs.

Adjectives and adverbs are the bane of metal writing. “Dark clouds darkened the gloomy sky as the desperate men of Pounder grimly prepared to do ghastly battle against myriad legions of wimps and posers”. Small wonder that I try to avoid reading about metal.

. . .

6. Show, don’t tell.

This relates to #7. Adjectives and adverbs are often just shorthand, a way to tell without showing.

For example:

He was sad.

He soaked his beer with tears.

It’s clear which sentence is more evocative. Don’t just say that he’s sad – show it!

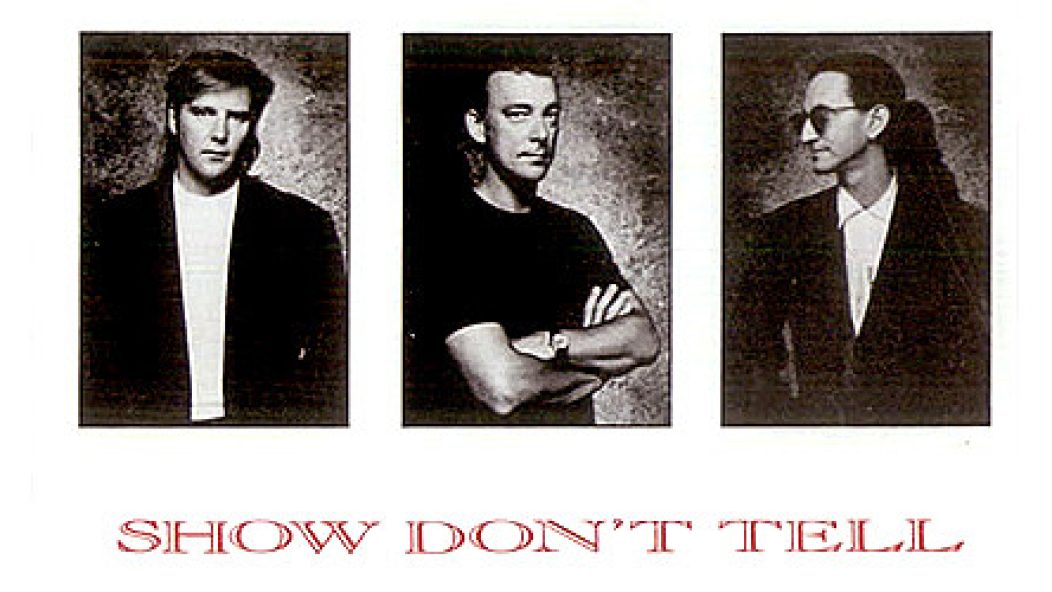

(Also, “Show Don’t Tell” is the first Rush song I ever heard.)

. . .

5. If it can be cut, it should be cut.

Writing ideally has two phases before it reaches the reader: writing and editing. Once you have words on a page, someone should quality-check it. Sometimes that someone is a professional. But if you want to be a good writer, you should be a competent editor. The better your work is when it reaches an editor’s desk, the less work he/she will have to do – and the more work you will get (in a good way).

Crucial to editing is removing words – adjectives, adverbs, cutting the passive voice down to a lean, active one. If you have any doubt about a word, axe it. “All killer, no filler” applies to words like it does to music.

. . .

4. Read your work out loud.

If you can’t/won’t do this literally, at least do so mentally.

Very few writers’ work sounds good out loud. But there’s a reason why people talk about a writer’s “voice”. Writers wield language just like speakers do. Maybe humans process reading and speech in different parts of the brain; I don’t know. But I do know that words, no matter their form, compete for people’s time and attention. People can only process so many words in a day. As a writer, you must cut through the noise and command attention.

A great way to do so is through writing that “sounds” good. In other words, have rhythm. Writing and music aren’t that different. Good music should breathe. It should have dynamics. It should have tension and release.

Likewise, don’t throw walls of text or never-ending sentences at readers. No one likes to listen to a motormouth. Break up wordy passages with short sentences. Finish paragraphs. Pay attention to the sounds of words. I’m sure many people read me just because they can understand me. I don’t talk like how I write – but I write like how someone might talk. People can get with that.

. . .

3. Break the rules only when you know you’re doing so.

Note that #5 violates #8. I used the passive voice – and I used it on purpose. I could have used the active voice: “If you can cut it, you should cut it”. But I followed #4: “If it can be cut, it should be cut” sounds better. #4 trumped #8. When I write and edit, I do such calculations constantly. If I break a rule, I know exactly why I’m doing it. You should be able to justify the existence of every word you write.

. . .

2. Practice, practice, practice.

Malcolm Gladwell popularized the 10,000-hour rule (see here and here). The short version: it takes 10,000 hours of work to become a top expert at something. Most people don’t need to become top experts in order to have fulfilling experiences with things. But my glass is half-empty, and every second that I live is a second closer to death. So I want every one of my hours to go towards 10,000 hours of something.

. . .

1. Practice, practice, practice.

I can’t stress this enough. Writing is a muscle. If you don’t work it, it grows limp. You can’t just drink yourself into delusions of grandeur and call yourself a writer. If I take even a day or two off from writing, I return to it feeling weak. (Ironically, doing this site has cut into my writing time so much that my writing has greatly suffered.) The pen (or keyboard) is an instrument, just like a guitar or piano. It won’t play itself. You must make it work for you.

I am fortunate to have had editors who’ve allowed me to be incompetent for years on their dime as I learned my craft. When you start out at anything, you will suck at it. But if someone gives you the opportunity to be bad, with the expectation that you’ll be good later – grab it, and don’t let go until you’re 10,000-hours-good.

. . .