A guide to writing about music, pt. 2: Thinking

. . .

This is the second part of a three-part series on writing about music. Part one discussed the necessity of reading in order to improve one’s writing. This part discusses how to have interesting things to say about music.

Note that I am not setting out a “right” way to think. I favor flexible approaches to problem-solving, and writing about music is a problem to solve: how to talk intelligently about music, yet keep your reader’s attention.

I’ve written about music for six years, and I didn’t have interesting things to say until approximately year four. Hopefully, you won’t take so long to become an interesting writer. Here are 10 tips to help make that happen.

. . .

10 TIPS FOR THINKING ABOUT MUSIC

. . .

10. Opinion doesn’t matter; insight does.

One of the Internet’s worst faults is that it atomizes attention spans. People engage in anonymous hit-and-run attacks of “This rules/sucks”, and believe that worthy of effort. No need even to email friends now; just “like” their Facebook ramblings!

Unfortunately, “rules/sucks” is the level on which 99% of humanity operates. It’s worthless except to bean counters. Richard Schickel, a film critic, wrote a brilliant article on criticism that I try to heed. He said:

Opinion – thumbs up, thumbs down – is the least important aspect of reviewing. Very often, in the best reviews, opinion is conveyed without a judgmental word being spoken, because the review’s highest business is to initiate intelligent dialogue about the work in question, beginning a discussion that, in some cases, will persist down the years, even down the centuries.

This quote contains an important point: saying that something rules or sucks is redundant, because the writer’s tone will convey that message anyway.

I would rather disagree with a well-reasoned, well-written review than agree with a poorly-reasoned, poorly-written one. The former educates, and the latter wastes time. Agreement is overrated, anyway. A roomful of people agreeing makes for terrible conversation.

. . .

9. Avoid the consumer guide mentality.

That is, unless you are paid to be a consumer guide. In this piece – another great guide for budding critics – Leonard Pierce points out that being a consumer guide is really the only way music writers make money now. Consumers – not readers, not people, but consumers – just want the star rating so they know what to buy/download. They could care less if the writer has something interesting to say. Again, this level of discourse only benefits bean counters. The world needs more readers and fewer consumers. Help make that happen.

. . .

8. A description is not a review.

I see many album reviews that go like this: “X album falls in Y genre, with influences from Z genre. It’s good for Y genre, with fast parts and slow parts and some medium parts. It runs a little long, but fans of the genre should pick it up anyway”.

Not only does this fall victim to the consumer guide mentality, it’s also boring as hell. Additionally, people now can stream and download music to hear for themselves. They don’t need critics anymore to tell them what music sounds like. Of course, descriptions are useful to support arguments, or to help establish the field of inquiry. But a description alone is not an inquiry, and, as I discuss below, inquiry is crucial to writing about music.

. . .

7. When discussing music, there is no such thing as objectivity.

Every accusation of biased reviews is true. That’s because every person comes with biases: environment, personal history, sensory organs. No one else has my personal history and my ears. Together those things provide an inescapable subjective framework through which I perceive things. One could be objective if one were a robot – and that might be true of some writers – but luckily most people, even music writers, have personalities.

. . .

6. However, recognize your biases.

A bias is a prejudice, something that affects your judgment. Any sort of predilection is a bias. Someone who’s a die-hard death metal fan may be the worst person to review death metal – because he’s a die-hard fan. He’s pre-disposed to like it, he may not think critically about it, and if his only reference points are other death metal records, his writing will likely be coddling and cliquish.

One of the strongest biases is personal association. Do not accept money to pass judgment on a musician whom you know. That is a great way to jeopardize both that relationship and your professional integrity.

. . .

5. “Great minds discuss ideas. Average minds discuss events. Small minds discuss people”. – Eleanor Roosevelt

This correlates with the sports maxim, “Play the ball, not the player”. One of my greatest frustrations regarding Varg Vikernes is that the very mention of his name yields kneejerk reactions (see “rules/sucks” discussion above), yet his music does not reflect the controversial aspects of his private life. Every Varg Vikernes discussion devolves to the same thing: “Burzum rules!/ Vikernes is scum!”. It’s all quite tiresome. No one shares anything, no one learns anything, yet many mouths flap.

. . .

4. Analogize to other areas of life.

A good writer can make anything interesting. A bad writer can make anything uninteresting. I would rather read, say, a New York Times article on Peruvian cooking, something that usually doesn’t concern me, than a typical blog post about metal, something that concerns me daily. This is because the NYT writer likely knows how to ease the reader into unfamiliar territory and point out sights along the way.

So Peruvian cooking is interesting because it’s a process. Many other things are processes, including making music. (In an interview, Carlos Santana once compared playing a live set to serving a meal.) Draw inspiration from everywhere. Compare music to other artforms, like photography, painting, and cinema, and even seemingly unrelated topics like athletics or urban planning. Different people often solve diferent problems using the same tools. Find those connections, and you’ll draw from a much richer set of information than genre-specific references.

. . .

3. Learn the nuts and bolts of music.

You don’t have to become a musician. After all, if you were truly a musician, you would not be a music writer. But learn what constitutes Western music (since that’s likely what you’ll be writing about). Learn some music theory. Try to play the drums. You will have much more respect for musicians once you discover that you can’t do what they do. You wouldn’t trust a car reviewer who doesn’t know how engines work. Likewise, don’t trust a music reviewer who can’t tell you how music works.

. . .

2. Determine the essence of the music.

This is my main inquiry when I write about music. What makes something what it is? Often it’s not what’s obvious. Often it’s a little detail that sums up the whole. For Tombs, that might be Mike Hill’s moan. For Repulsion, it might be Scott Carlson’s emphatic vocal patterns. Drill down and find the whatness of things. Sure, Kill ‘Em All is the tipping point between NWOBHM and thrash. But it’s much more interesting and insightful to say that Kill ‘Em All is one of the purest blasts of adolescent energy ever recorded. Once you establish that idea, adolescence, you can go places with it. Simply discussing NWOBHM and thrash leads one to Wikipedia.

. . .

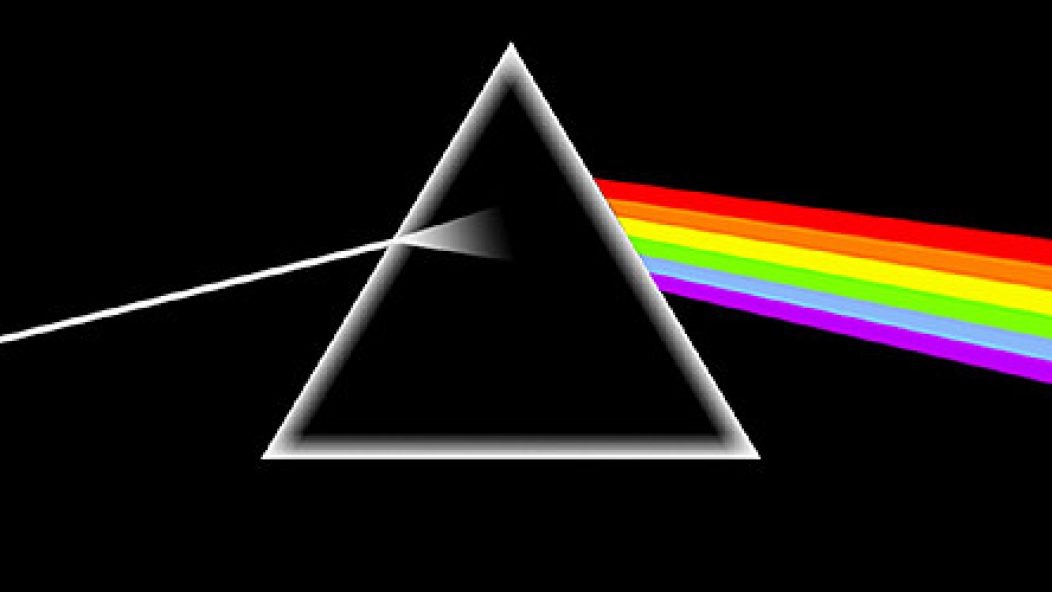

1. Seek to refract.

Abandon the idea of being an authority on your subject. That is arrogant and likely futile. Someone else will always know more than you. Instead, embrace being a transparent vessel for ideas stemming from your subject. The inquiry should start, not stop with you. As music inspired you to write, so should your writing inspire others to think.

. . .